2019 Annual Food Fraud Report published by EU Commission

On 18 May 2020, the EU Commission’s Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety ("DG SANTE") published the 2019 Annual Report in respect of the EU Food Fraud Network and the Administrative Assistance and Cooperation System - Food Fraud ("the Report").

Established in 2013, the EU Food Fraud Network is made up of competent authorities designated by each EU Member State (as well as Switzerland, Norway and Iceland) along with the EU Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol), who are required to provide administrative assistance to enable the exchange of information on suspected cross-border violations of EU agri-food chain legislation. The network works in close consultation with the Knowledge Centre for Food Fraud and Quality (KC-Food), which is collectively operated by the Commission's science and knowledge service, the Joint Research Centre (JRC) and the various EU Departments with responsibility for regulating the feed-food chain and protecting consumer rights.

Created in 2015 and managed by the Commission, the Administrative Assistance and Cooperation System - Food Fraud ("the AAC-FF System") is a dedicated IT tool that provides a platform for members of the EU Food Fraud Network to exchange information on non-compliances and potential intentional violations of the EU agri-food chain legislation.

What is Food Fraud?

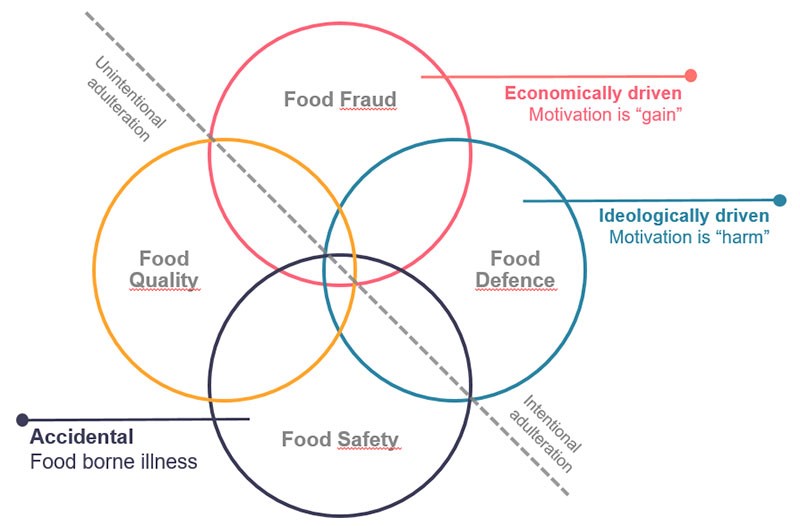

Although not specifically defined, the general term "food fraud" can be taken as encompassing a wide variety of activities referred to (adopting the wording contained in Regulation (EU) 2017/625) as "fraudulent or deceptive practices" by businesses or individuals for the purpose of gaining some form of undue advantage and/or causing harm.

The EU Commission has also developed a criteria for identifying instances of food fraud that accounts for features such as identifiable violations of EU rules (as set out in Article 1(2) of Regulation (EU) 2017/625), deception, economic gain and intention.

Notwithstanding the complex nature of food fraud and its consequences, the growing threat posed by these types of fraudulent and deceptive practices is well recognised, with various high-profile scandals and incidents highlighting the economic and public health threat posed by such fraudulent practices to consumers throughout the EU and the wider world:

- 1981: Fraud involving rapeseed oil intended for industrial use being sold as cooking oil affects approximately 20,000 people and leads to between 370 and 835 fatalities in Spain.

- 1999: Dioxin scandal in Belgium results in widespread economic damage throughout the EU.

- 2008: Milk adulterated with melamine in China results in more than 50,000 babies affected, including six suspected fatalities.

- 2012-14: Methanol poisoning from the sale of illegal spirits leading to approximately 59 casualties in Czech Republic and Poland.

- 2013: Horsemeat detected in beef products throughout the EU as a result of initial testing carried out the by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland.

- 2017: Eggs on sale throughout EU found to be contaminated with the insecticide Fipronil.

- 2019: The slaughter and export for sale of beef from sick Polish cows to various EU Member States.

The Report

The Report describes how network members generated a total of 292 requests for administrative assistance and cooperation through the system in 2019 – an increase from 234 in 2018. Based on data analysis and its own lines of inquiry, the Commission itself also submitted 70 such requests calling on different countries to investigate and follow-up on same.

In terms of product categories, changes were observed amongst the top 10 most notified categories compared to 2018. ‘Fats and oils’ were the subject of 29 requests for cooperation in 2018. This represented the third-most notified group after ‘fish’ (45) and ‘meat products’ (41). However, in 2019 ‘fats and oils’ became the most notified category (44) placing ‘olive oil’ as the most notified product in the system. Compared to 2018, ‘poultry meat’, ‘cereals and bakery products’ and ‘nuts and nut products’ also entered the top 10 product categories notified by the network in the system, pushing out ‘dietetic foods and food supplements’, ‘animal by-products’ and ‘honey and royal jelly’.

In terms of categories of non-compliance, the AAC-FF system groups suspected violations into five main groups:

- Mislabelling: Products that contain misleading information on the label. For example, there were a high number of requests for cooperation in respect of products that were deceitfully labelled, as ‘organic’ notwithstanding the presence of pesticide residues, as well as cases of products labelled as extra virgin olive oil adulterated with lampante olive oil.

- Replacement / dilution / addition / removal: This often relates to a product’s species being substituted for a different one such as beef being replaced with a cheaper alternative such as pork or horsemeat. Other real word examples draw from the data involving plants and vegetables include oregano diluted with olive leaves, or Basmati rice diluted with other cheaper types of rice.

- Unapproved Treatments/Processes: Examples of requests made in 2019 concerned unapproved treatment of fruits and vegetables with pesticides (unauthorised chemical treatment) and the treatment of tuna with nitrite or carbon monoxide, substances used to enhance the colour of the product in order to lead the customer into believing that it is of better quality.

- Documents: Requests from 2019 regarding falsified documentation were mainly related to meat and fish products. For example, Member States notified a recurrent problem regarding consignments of meat from animals with tampered passports and forged electronic chips, delivered either without the required documentation or with falsified records.

- Intellectual Property Rights: The EU has its own set of ‘geographical indication’ (GI) marks designed to protect the value vesting in the names of products whose characteristics have a particular connection to the specific regions where they are produced. These marks (PDO/PGI/TSG) and protected names, which are supposed to enable consumers to distinguish particularly unique and high quality products, can be used fraudulently and this has been found to be the case particularly in relation to wines and olive oils.

It is also useful to note that out of 292 requests in 2019, the overall number of violations identified was 431, so most requests into the system involved more than one type of non-compliance category. The most common non-compliance was ‘mislabelling’ which accounted for 47.3% of the total of violations reported in the system.

Coordinated Activities

The most interesting parts of the Report are arguably a set of case studies describing joint operations targeting fake and substandard food and beverages that the food fraud network is engaged in with Europol. For example, in 2019 the network was engaged in the eighth phase of operation OPSON, a set of coordinated actions led by the Commission and various EU Member States in relation to organic products (the Commission), coffee (Germany) and 2,4-Dinitrophenol DNP (a dangerous compound used as a dieting aid) (UK). Interesting further examples provided in the report include a joint-operation between UK and Spanish authorities targeting the adulteration of saffron, and a coordinated action by the Commission in relation to the illegal trade in European Eel.

Conclusion

The Report stands as both a useful snapshot of work across the EU to tackle food fraud, a problem that is expected to grow in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as a very interesting and easily digestible insight into specific operations and actions taking place throughout the EU. This is also an area of growing interest given the relatively recent coming into force of Regulation (EU) 2017/625 in December 2019. This legislation makes provision for the implementation of the Integrated Management System for Official Controls (IMSOC) and requires Member States to report all agri-food fraud suspicions of cross-border nature through the AAC-FF system. Regulation (EU) 2017/625 also extends the scope of these notifications to all areas covered by it (e.g. animal or plant health, animal welfare, certain environmental aspects). These development are expected to further enhance the capabilities of the existing EU food fraud system’ to detect and counter potential fraudulent activities, a welcome development that can be tracked in further reports.

The Report is available here.