Locations

The US Supreme Court recently handed down a decision on a copyright infringement case, Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (05/18/2023) (supremecourt.gov).

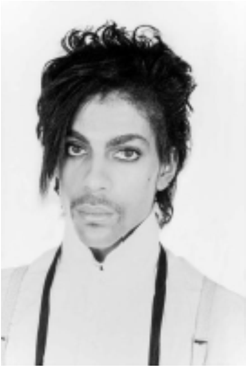

The dispute concerned photographs of Prince, a famous musician in the United States, which were taken by Goldsmith, the plaintiff in the dispute, in 1981 when Prince was not particularly famous. After taking the photographs, Goldsmith licensed them to various magazines for use as covers. All the magazines credited Goldsmith as the photographer, and some paid royalties to Goldsmith.

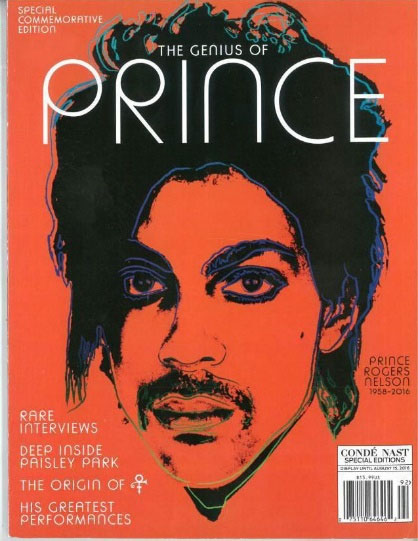

Based on the photographs taken by Goldsmith, Andy Warhol created a series of Prince works. The original work of Goldsmith is illustrated on the left, and the new work of Andy Warhol, the subject of the dispute, is illustrated on the right ("Orange Prince").

The Prince series including the Orange Prince passed to the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF), the defendant in the present dispute, after Andy Warhol died. In 2016, AWF licensed a magazine to publish the Orange Prince for $10,000. Goldsmith was unaware of the licensing deal until she saw the Orange Prince in the magazine.

The main point in dispute was whether AWF’s unauthorized use of Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph was fair use, and more specifically, whether the first factor provided in 17 U.S.C. $ 107 (set out below) favored for or against AWF’s fair use defense.

17 U.S.C. § 107 provides the fair use defense to copyright infringement. Besides enumerating fair use examples for specific purposes like criticism, comment, news reporting, etc., the article also prescribes a general rule of determining whether the use made of a work is fair use, taking into account four factors[1].

The first factor is “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.”

In analyzing this factor, the District Court investigated whether the “new work” was transformative as compared to the original works by looking at whether the new works add new expression to the original one. In other words, the District Court focused on how the “new work” was compared with the original work, and whether the differences, if any, were transformative.

The District Court held that the new work was “transformative” because, “looking at them and the photograph ‘side-by-side’, they ‘have a different character, give Goldsmith’s photograph a new expression, and employ new aesthetics with creative and communicative results distinct from Goldsmith’s.” In particular, the District Court determined that the (new) work “can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” such that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince.”

The dissenting opinion in the Supreme Court took a similar approach in assessing the “purpose and character” of a copier’s use by asking: “does the work add something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the original with new expression, meaning or message?” When it did so to a significant degree, the dissenting justices observed that the work would be considered transformative and the first factor of the fair use test would favor the copier.

The dissenting justices investigated what Warhol did to the original work, and found that “Warhol converted the cropped photo into a higher-contrast image, incorporated in to a silkscreen and that image isolated and exaggerated the darkest details of Prince’s head; and it also reduced his ‘natural, angled position’, presenting him in a more face-forward way, and thereby causing ‘materially distinct’ visual differences between the new work and the original work in their ‘composition, presentation, color palette, and media’, and the change in form brought an undisputed change in meaning…”. With these significant differences, the dissenting opinion held that Warhol had effected a transformation and therefore the first fair use inquiry should favor him.

However, the majority opinion in the Supreme Court focused on the use of the work rather than the work itself. The majority opinion considered the major inquiry of the first factor was “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original, and “the larger the difference, the more likely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use, while the smaller the difference, the less likely”.

Instead of centering around the comparison between the new work and the original work, the majority opinion considered whether the allegedly infringing use had a sufficiently similar purpose to that of the original work so that it was likely to substitute or supplant the original work.

Here, the majority justices found that the specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph alleged to infringe her copyright was AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to a magazine named Condé Nast. The majority considered that Orange Prince shared substantially the same purpose as the original photograph in respect of use, and AWF’s licensing of the Orange Prince image superseded the objects of Goldsmith’s photograph. Accordingly, the majority held that the first fair use factor favored against the defendant.

2. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994)

Campbell is a leading case on the fair use doctrine, and was relied upon by the litigants in the Goldsmith case. Campbell is both respected and clarified by the Supreme Court in this case.

The Campbell court considered that the central purpose of the first factor was to see “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is ‘transformative.’”

It is arguable that this mixes up two standards in one paragraph. The first part investigates on the purpose of the new work to see whether it is different from or merely superseding that of the original work; but, the second part switches the focus back to the “new work” itself to see whether the new work is transformative. As what the District Court and dissenting justices did in the Goldsmith case, tasks of assessing whether a new is transformative is entirely different by comparing work to work to see if any significant changes are made to the new work by the copier, whether it’s change in form, change in meaning, change in feel or change in style. By “in other words”, the court appears to set up a different criterion of deciding the first factor.

AWF relies upon the transformative work standard of Campbell and bases its arguments thereon in further elaborating how the new work alters the original work by adding new expression, meaning, or message. As mentioned above, this reasoning process is followed by the District Court and the dissenting opinion of the Supreme Court.

The majority opinion of Supreme Court in the Goldsmith case defers to one part, and clarifies the other part; the majority opinion agrees that Campbell did describe transformative use as such, but further clarifies that it cannot be read to mean that §107 (1) weighs in favor of any use that adds new expression, meaning, or message, because otherwise, it would “swallow copyright owners’ right to prepare derivative works.”

The “superseding purpose” part is relied upon by the Supreme Court in coming to the conclusion that “the use of an original work to achieve a purpose that is the same as, or highly similar to, that of the original work is more likely to substitute for or ‘supplant’ the work”.

In making the transition from the focus of the transformativeness of works to the transformative purpose of use, the Supreme Court inferred from Campbell that the same copying may be fair when used for one purpose but not another. And, further based on the plain meaning of §107, the court considers that the fair use provision, and the first factor in particular, requires an analysis of the specific “use” of a copyrighted work that is alleged to be “an infringement”.

Additionally, the court cites Campbell to stress the importance of targeting the original work in the new use in assessing whether the new use is transformative or not. In particular, the court distinguishes the fair use defense in the present case from parody in Campbell; “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value” because it can provide social benefit by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one, whereas, in the present case, AWF’s use of the new work simply copied the subject of the copyrighted work, but did not target Goldsmith’s original work in the use, and therefore should not be protected by fair use from the perspective that it did not have the justification of social benefit.

3. Comparison with Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc. 141 S. Ct. 1163 (2021)

The Supreme Court decided another case on the fair use doctrine in 2021: Oracle vs. Google.

In the Oracle case, the court in a majority decision decided that Google’s copy of the API of Java SE was fair use. The court analyzed all four fair use factors in making the decision. In respect of the first factor, the court considered that the purpose of Google’s use of Java API was to create a new product to be installed in Android-based smart phone platforms, which was different from Oracle’s use of the Java program. Comparatively, in the Goldsmith case, the court considered the purpose of AWF’s licensing of the new work to a magazine to illustrate a story about Prince was identical to the copyright owner’s use of the original work, even though it might be a different magazine.

To conclude, the Goldsmith case makes a notable development to the Supreme Court’s prior decisions over fair use defense in copyright infringement by clarifying the meaning of “transformativeness” rule established in Campbell case and shifting the focus of investigation of “transformativeness” from comparing the works to comparing the purpose of using the works, which from our perspective brings the first fair use factor closer to its literal meaning of USC § 107. The first factor under USC § 107 explicitly says “purpose and character of the use”, not about the works. Comparison of the works, whether being similar or not, is the major task of copyright infringement, but probably not of fair use defense.

Based on the photographs taken by Goldsmith, Andy Warhol created a series of Prince works. The original work of Goldsmith is illustrated on the left, and the new work of Andy Warhol, the subject of the dispute, is illustrated on the right ("Orange Prince").

| Goldsmith’s original work | Andy Warhol’s new work | |

|

|

The Prince series including the Orange Prince passed to the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF), the defendant in the present dispute, after Andy Warhol died. In 2016, AWF licensed a magazine to publish the Orange Prince for $10,000. Goldsmith was unaware of the licensing deal until she saw the Orange Prince in the magazine.

The main point in dispute was whether AWF’s unauthorized use of Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph was fair use, and more specifically, whether the first factor provided in 17 U.S.C. $ 107 (set out below) favored for or against AWF’s fair use defense.

- Courts’ split: transformative “works” or transformative “use”?

17 U.S.C. § 107 provides the fair use defense to copyright infringement. Besides enumerating fair use examples for specific purposes like criticism, comment, news reporting, etc., the article also prescribes a general rule of determining whether the use made of a work is fair use, taking into account four factors[1].

The first factor is “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.”

In analyzing this factor, the District Court investigated whether the “new work” was transformative as compared to the original works by looking at whether the new works add new expression to the original one. In other words, the District Court focused on how the “new work” was compared with the original work, and whether the differences, if any, were transformative.

The District Court held that the new work was “transformative” because, “looking at them and the photograph ‘side-by-side’, they ‘have a different character, give Goldsmith’s photograph a new expression, and employ new aesthetics with creative and communicative results distinct from Goldsmith’s.” In particular, the District Court determined that the (new) work “can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” such that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince.”

The dissenting opinion in the Supreme Court took a similar approach in assessing the “purpose and character” of a copier’s use by asking: “does the work add something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the original with new expression, meaning or message?” When it did so to a significant degree, the dissenting justices observed that the work would be considered transformative and the first factor of the fair use test would favor the copier.

The dissenting justices investigated what Warhol did to the original work, and found that “Warhol converted the cropped photo into a higher-contrast image, incorporated in to a silkscreen and that image isolated and exaggerated the darkest details of Prince’s head; and it also reduced his ‘natural, angled position’, presenting him in a more face-forward way, and thereby causing ‘materially distinct’ visual differences between the new work and the original work in their ‘composition, presentation, color palette, and media’, and the change in form brought an undisputed change in meaning…”. With these significant differences, the dissenting opinion held that Warhol had effected a transformation and therefore the first fair use inquiry should favor him.

However, the majority opinion in the Supreme Court focused on the use of the work rather than the work itself. The majority opinion considered the major inquiry of the first factor was “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original, and “the larger the difference, the more likely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use, while the smaller the difference, the less likely”.

Instead of centering around the comparison between the new work and the original work, the majority opinion considered whether the allegedly infringing use had a sufficiently similar purpose to that of the original work so that it was likely to substitute or supplant the original work.

Here, the majority justices found that the specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph alleged to infringe her copyright was AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to a magazine named Condé Nast. The majority considered that Orange Prince shared substantially the same purpose as the original photograph in respect of use, and AWF’s licensing of the Orange Prince image superseded the objects of Goldsmith’s photograph. Accordingly, the majority held that the first fair use factor favored against the defendant.

2. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994)

Campbell is a leading case on the fair use doctrine, and was relied upon by the litigants in the Goldsmith case. Campbell is both respected and clarified by the Supreme Court in this case.

The Campbell court considered that the central purpose of the first factor was to see “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is ‘transformative.’”

It is arguable that this mixes up two standards in one paragraph. The first part investigates on the purpose of the new work to see whether it is different from or merely superseding that of the original work; but, the second part switches the focus back to the “new work” itself to see whether the new work is transformative. As what the District Court and dissenting justices did in the Goldsmith case, tasks of assessing whether a new is transformative is entirely different by comparing work to work to see if any significant changes are made to the new work by the copier, whether it’s change in form, change in meaning, change in feel or change in style. By “in other words”, the court appears to set up a different criterion of deciding the first factor.

AWF relies upon the transformative work standard of Campbell and bases its arguments thereon in further elaborating how the new work alters the original work by adding new expression, meaning, or message. As mentioned above, this reasoning process is followed by the District Court and the dissenting opinion of the Supreme Court.

The majority opinion of Supreme Court in the Goldsmith case defers to one part, and clarifies the other part; the majority opinion agrees that Campbell did describe transformative use as such, but further clarifies that it cannot be read to mean that §107 (1) weighs in favor of any use that adds new expression, meaning, or message, because otherwise, it would “swallow copyright owners’ right to prepare derivative works.”

The “superseding purpose” part is relied upon by the Supreme Court in coming to the conclusion that “the use of an original work to achieve a purpose that is the same as, or highly similar to, that of the original work is more likely to substitute for or ‘supplant’ the work”.

In making the transition from the focus of the transformativeness of works to the transformative purpose of use, the Supreme Court inferred from Campbell that the same copying may be fair when used for one purpose but not another. And, further based on the plain meaning of §107, the court considers that the fair use provision, and the first factor in particular, requires an analysis of the specific “use” of a copyrighted work that is alleged to be “an infringement”.

Additionally, the court cites Campbell to stress the importance of targeting the original work in the new use in assessing whether the new use is transformative or not. In particular, the court distinguishes the fair use defense in the present case from parody in Campbell; “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value” because it can provide social benefit by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one, whereas, in the present case, AWF’s use of the new work simply copied the subject of the copyrighted work, but did not target Goldsmith’s original work in the use, and therefore should not be protected by fair use from the perspective that it did not have the justification of social benefit.

3. Comparison with Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc. 141 S. Ct. 1163 (2021)

The Supreme Court decided another case on the fair use doctrine in 2021: Oracle vs. Google.

In the Oracle case, the court in a majority decision decided that Google’s copy of the API of Java SE was fair use. The court analyzed all four fair use factors in making the decision. In respect of the first factor, the court considered that the purpose of Google’s use of Java API was to create a new product to be installed in Android-based smart phone platforms, which was different from Oracle’s use of the Java program. Comparatively, in the Goldsmith case, the court considered the purpose of AWF’s licensing of the new work to a magazine to illustrate a story about Prince was identical to the copyright owner’s use of the original work, even though it might be a different magazine.

To conclude, the Goldsmith case makes a notable development to the Supreme Court’s prior decisions over fair use defense in copyright infringement by clarifying the meaning of “transformativeness” rule established in Campbell case and shifting the focus of investigation of “transformativeness” from comparing the works to comparing the purpose of using the works, which from our perspective brings the first fair use factor closer to its literal meaning of USC § 107. The first factor under USC § 107 explicitly says “purpose and character of the use”, not about the works. Comparison of the works, whether being similar or not, is the major task of copyright infringement, but probably not of fair use defense.

[1] Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106 and 106 A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include-

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.