Locations

Of all the privacy developments that have hit the headlines this year, arguably none – not even the coming into effect of the CCPA, developments related to the LGPD in Brazil, or the ongoing Brexit adequacy saga – have been as impactful as the Court of Justice of the European Union’s ruling in Schrems II on 16 July.

This ruling declared invalid reliance on the EU-US Privacy Shield as a lawful mechanism for exporting data to the US, due to concerns about surveillance by US state and law enforcement agencies (and with the subsequent effect that the Swiss-US Privacy Shield has also suffered a similar fate in the past day). It upheld the EU Standard Contractual Clauses (“SCCs”) as a lawful mechanism for data exports, but subject to an assessment of the recipient territory’s laws and the potential need to put in place “supplementary measures” to ensure that exported EU data remains protected to a standard that is “essentially equivalent” with EU law. But enough of that: if you want to read about the background to the case or a legal analysis of the ruling, then see our earlier blog posts - Background on CJEU "Schrems II" Case and Schrems II Judgement Day.

Depending on the commentary you read, the ruling either spells the end of international data transfers to the US, is a bump in the road that will be fixed in time by new (and long overdue) EU Standard Contractual Clauses or a new “Privacy Shield 2.0”, or is all a big fuss about nothing that won’t have any meaningful impact at all. There’s a lot of theorising on all sides of the debate, but what will be the practical reality? How are organisations actually responding?

It was with a view to answering those questions that Fieldfisher decided to launch a survey on the practical impacts of Schrems II. Plenty of you replied (and thank you to everyone who did), and details of the survey responses – together with our analysis about what this means – are set out below.

How was the survey run?

But first, the boring bit: explaining our survey methodology. The survey was created on SurveyMonkey and made publicly available online. It comprised 9 multiple choice questions in total, each of which you can see below. Participants were invited to respond to the survey through LinkedIn and through our blog.

We set the survey to run anonymously, in the sense that we did not ask any participants to identify themselves, so we do not know the identity of any participants who responded, but it is reasonable to assume (due to the wide reach of our blog and social media contacts) that respondents from organisations both within and without the EEA and UK will have participated across a variety of sectors. We did turn on a survey feature that prevented the same respondent from completing the survey twice.

In total, we received 138 responses – and, after the first 30 – 40 responses, clear trends had started to develop. Subsequent responses up to the point of closing the survey (today) tended to reinforce the trends we saw in the early responses. A full copy of the survey responses is available here: Schrems II Impacts Report

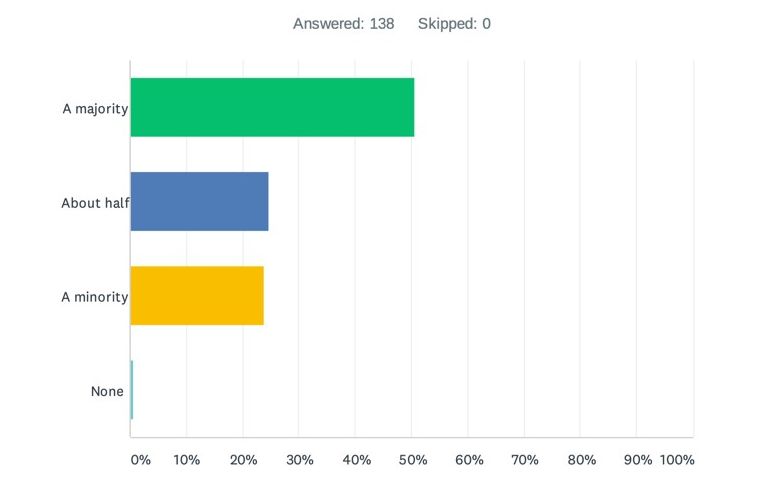

Question 1: What proportion (roughly) of the data processors used by your organisation are US-based or based in non-EEA/non-UK territories?

Of the responses received to this question, approximately 75% indicated that half or more of their data processors are based in the US or non-EEA/non-UK territories (around 50% saying the majority and a further 25% saying about half).

This illustrates why the Schrems II ruling is so impactful: if the survey results we have seen are illustrative of wider industry as a whole, there will be an awful lot of organisations who are now having to transition their data flows away from reliance on the Privacy Shield across to SCCs.

Even where organisations are already relying on the SCCs, the Schrems II ruling suggests they now need to consider undertaking transfer impact assessments to assess whether those transfers meet the “essential equivalence” test and, if not, to implement “supplementary measures”. That inevitably means a lot of legacy vendor relationships will be revisited – and new vendor relationships will be subject to much closer investigation and scrutiny going forward.

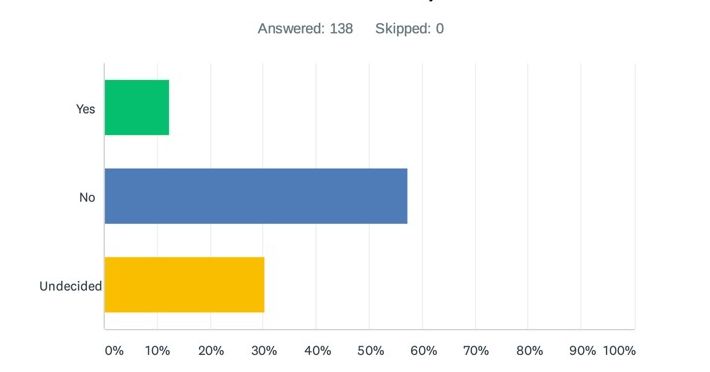

Question 2: In light of the Schrems II ruling, does your organisation intend to *reduce* use of US-based or non-EEA/non-UK data processors (either now or over time)?

Tellingly, only a small minority of respondents answers “yes” to this question – just 12%. The remaining 88% indicated they did not intend to reduce their data exports to the US or to non-EEA/non-UK jurisdictions (57%) or were undecided (30%). Clearly, the volume of undecided responses – totalling around 1/3 of the responses received – indicates that future regulatory guidance and enforcement will play a critical role to the actions that organisations take.

What else can you read from this? Arguably this: that no matter what the law says, data transfers are an inevitability of modern technologies and the Internet. Attempting to regulate in a way that restricts those transfers could simply result in widespread non-compliance across organisations who have little meaningful alternative. Regulatory guidance therefore needs to identify solutions, not barriers.

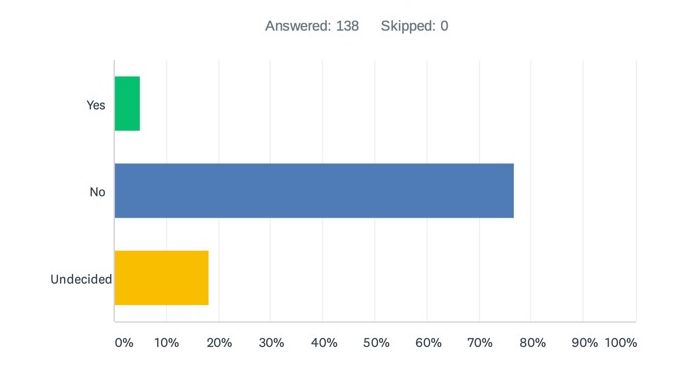

Question 3: In light of the Schrems II ruling, does your organisation intend to *cease* use of US-based or non-EEA/non-UK data processors (either now or over time)?

A more loaded question than question number 2, and only 5% responded that they intend to cease US or non-EEA/non-UK data exports – presumably then keeping all data in the EEA/UK. The analysis for Question 2 applies equally here.

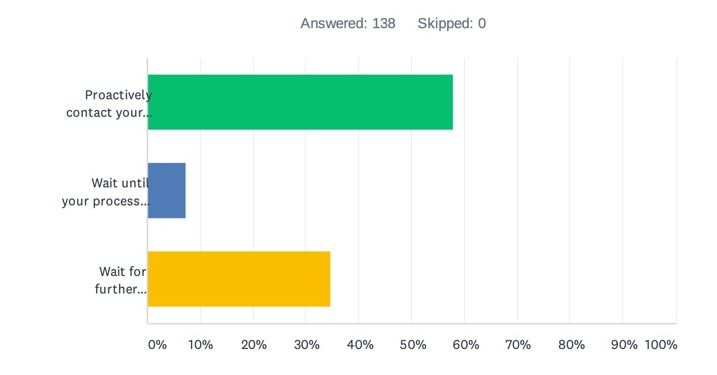

Question 4: If you previously relied on EU-US Privacy Shield commitments to transfer personal data to some or all of your US-based data processors, will you now:

(a) Proactively contact your processors and ask them to move to EU Standard Contractual Clauses, (b) Wait until your processors to contact you about moving to EU Standard Contractual Clauses or (c) Wait for further regulatory guidance before acting?

Overall, there was a leaning here towards controllers proactively contacting their US processors and asking them to move towards SCCs – approximately 58%. US vendors should therefore expect a flood of questions from their EEA/UK-based enterprise customers, to which they need to be ready to respond with data transfer FAQs (to avoid the need to prepare bespoke responses on a case-by-case basis), SCCs (to replace any prior reliance on the Privacy Shield), and an explanation of the “supplementary measures” they apply to protect customer data from surveillance.

Perhaps tellingly, though, around a third of respondents indicated that they would “wait for further regulatory guidance before acting”, suggesting that there is an air of reluctance amongst EEA/UK controllers to do anything before they have meaningful guidance from the EDPB as to what practical measures they should be taking. Those measures need to give practical guidance on how data transfers to the US can continue lawfully, given the criticality of US data transfers for most EEA/UK organisations (see questions 1 – 3 above), rather than simply adopting a “Fortress Europe” mentality which – for reasons already explained – will invite widespread non-compliance.

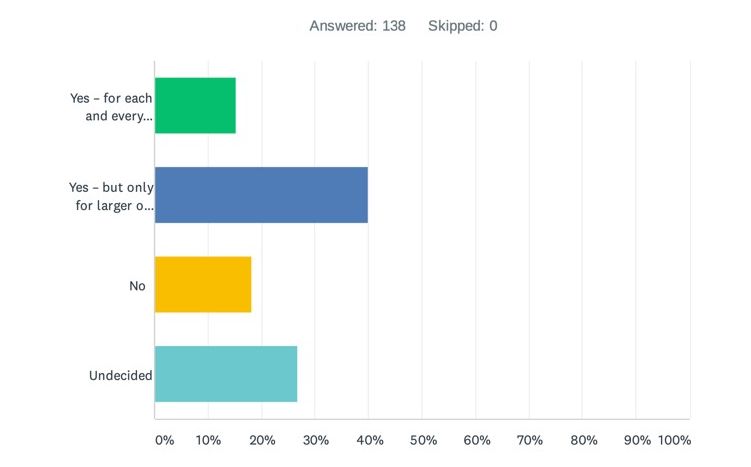

Question 5: When you transfer EEA/UK data outside of the EEA/UK, do you (or will you) in practice carry out a data transfer impact assessment for each such transfer?

A key element of the Schrems II ruling was the CJEU’s expectation that organisations must carry out case-by-case risk assessments for each non-EEA data transfer in which they engage, to ensure that the recipient will protect the data to a standard that is “essentially equivalent” with EU law. This assessment “must, in particular, take into consideration both the [SCCs] agree between the controller or processor … and the recipient of the transfer … and, as regards any access by public authorities of that third country to the personal data transferred, the relevant aspects of the legal system of that third country” (point 2 in the CJEU’s conclusions), including the rule of law, respect for human rights, relevant general and sectoral legislation, the existence of independent and effective supervisory authorities, the international commitments of the country concerned and… well, you get it: the list goes on and is well beyond the capabilities of any in-house privacy or legal team to assess.

So, with that in mind, the obvious question is whether organisations will carry out these transfer impact assessments in practice. Just over half of respondents indicated “yes” here, but with around 40% saying they would conduct such assessments “only for larger or more sensitive transfers”: the implication perhaps being that, for many routine, day-to-day, transfers, conducting transfer impact assessments is simply too much work and too complicated, and so won’t happen. After all, when the Commission conducts its own adequacy assessments of countries, this exercise is staffed by dedicated legal experts and takes well over a year: which in-house teams can boast that resourcing or timing flexibility?

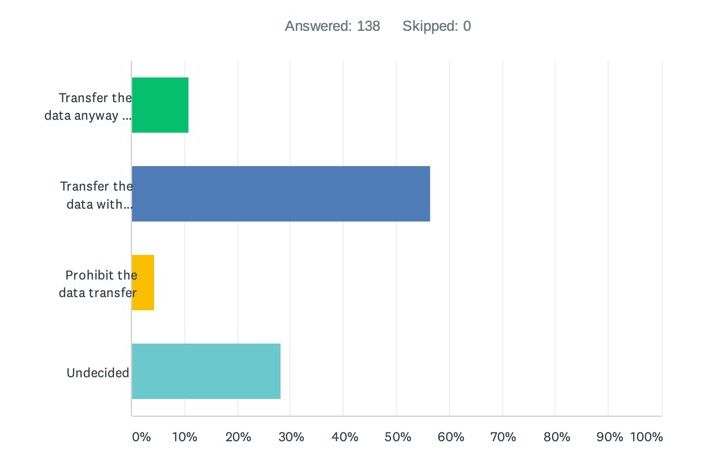

Question 6: If you carry out a transfer impact assessment, and determine that there is a risk that the EEA/UK data you transfer may be subject to non- EEA/non-UK government access, would you:

(a) Transfer the data anyway and document the risk, (b) Transfer the data with "supplementary measures" in place to protect the data, (c) Prohibit the data transfer, or (d) be undecided?

A mere 4% of respondents indicated here that they would prohibit the transfer – pointing to the theme above that data transfers to the US and wider non-EEA/non-UK countries will happen regardless of Schrems II.

However, some 57% of respondents did indicate they would endeavour to put in place “supplementary measures” and therefore clearly attempt to comply with the requirements of Schrems II – though much, obviously, will hang on what supplementary measures the EDPB decides might be suitable in this context. As to what organisations think should serve as supplementary measures, see the next question…

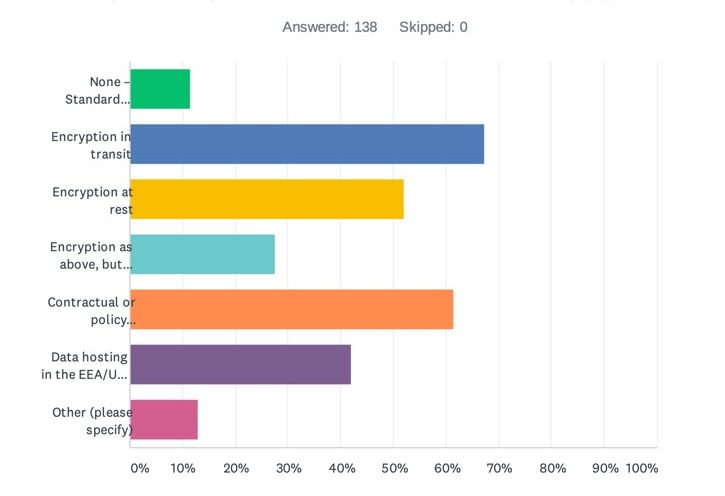

Question 7: If you transfer data to a non-EEA/non-UK data processor, what "supplementary measures" would you expect the processor to have in place to protect the data?

Well, this was perhaps the most interesting of all the questions and the responses most telling. Respondents were given the opportunity to choose as many multiple choice options as they wanted and to suggest their own additional measures.

Of the multiple choice options, respondents were invited to select one or more of: (i) None – Standard Contractual Clauses alone ought to be enough, (ii) Encryption in transit, (iii) Encryption at rest, (iv) Encryption as per (i) or (ii), but encryption key must be held by the customer (i.e. you), (v) Contractual or policy commitments from the processor limiting or prohibiting government access to data, (vi) Data hosting in the EEA/UK (to minimise non-EEA/UK data flows), or (vii) “Other” with the opportunity to specify what that “other” should be.

Let’s start at the beginning: there are the die-hards among respondents who clearly think the Schrems II ruling is just noise – a little under 12% said that SCCs alone should be sufficient without the need for supplementary measures. This view, however, is out-of-step with the ruling itself and, for that reason, very unlikely to find favour with any supervisory authorities.

The remaining responses could perhaps be characterised as “I’ll have one of each, please”, with a broad spread of responses to each supplementary measure proposed. Interestingly, the two standouts were “encryption in transit” (at 67%), perhaps reflecting concerns that without this data in transit could be intercepted under Executive Order 12333 or maybe just reflecting that this is an “easy win” on the basis that the majority of Internet transfers these days are encrypted using SSL or TLS, and “contractual or policy commitments from the processor limiting or prohibiting government access to data” (at just under 62%).

In terms of what contractual or policy commitments customers expect from their processors, this is unclear from the multiple choice responses provided, but it is likely a safe bet that EEA/UK controllers will expect their processors not to hand over data to government authorities on a voluntary basis and, even when compelled, to mount at least some resistance to disproportionate or vague data demands. Supervisory authority expectations will likely go further, however, and expect processors to commit to some degree of consultation with competent EU authorities – at least if the position they take on government data access for BCR applicants can now be read across to SCCs (see WP257 at 6.3).

Three other interesting points:

- There is a clear EEA/UK customer preference towards vendor hosting of customer data in the EEA/UK. This is interesting because, as any privacy professional will tell you, simply hosting data in the EEA/UK does not solve the data export problem if there is remote access to the data centre from outside the EEA/UK (e.g. for technical support or development purposes, as is often the case). Nevertheless, optically if nothing else, hosting data in the EEA/UK clearly finds favour with EEA/UK customers and therefore may feature in vendor data centre build-out strategies in future.

- Returning again to encryption, when vendors encrypt data on behalf of their customers, only a minority of customers (just under 28%) expect that they should hold the encryption key. This suggests a departure from regulator concerns that, if the vendor holds the encryption key, it could decrypt customer data for disclosure to law enforcement or state security bodies; however, it may also reflect the reality that, other than pure data hosting services, many customer data processing services simply cannot be provided (or cannot be provided easily) if the customer holds the encryption key.

- Finally, did any respondents have any other suggestions as to alternative “supplementary measures”? In a nutshell, not really. Some pointed to the need for a “case-by-case” assessment, but didn’t address possible measures that might result from such an assessment. Other respondents pointed to the use of pseudonymisation measures (hashing, tokenisation, etc.) and others pointed to adherence to recognised security standards (e.g. ISO standards etc.). Kudos to the one respondent who replied: “A magic wand!”

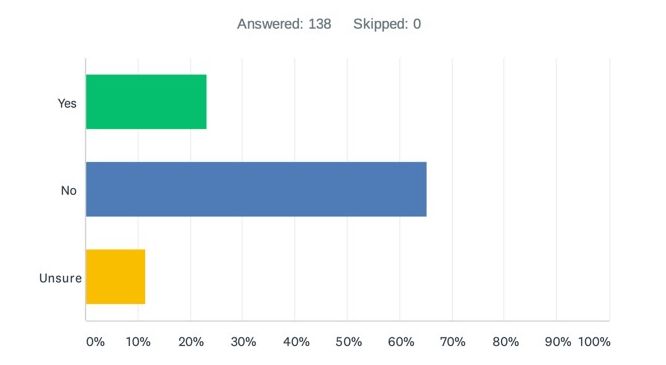

Question 8: Do you see data transfers of EEA/UK data to the US as inherently more risky than data transfers to recipients in other non-EEA/non-UK territories?

No, said 65% of respondents, with 12% being undecided and only 23% saying yes. Depending on which side of the fence you sit on, this response could be read as supporting the view that the US is being singled out for unfair treatment by the EU (contrast US surveillance with that reportedly undertaken in other “Five Eyes” territories, like the UK, Canada and New Zealand, for example, all of which are currently considered safe to receive EEA data) or it could be read as suggesting that respondents do not fully understand the scope of, or are otherwise ambivalent towards, US surveillance. But whichever way you look at it, the reality seems to be that the majority of respondents do not consider the US to be a greater risk than other non-EEA/non-UK countries.

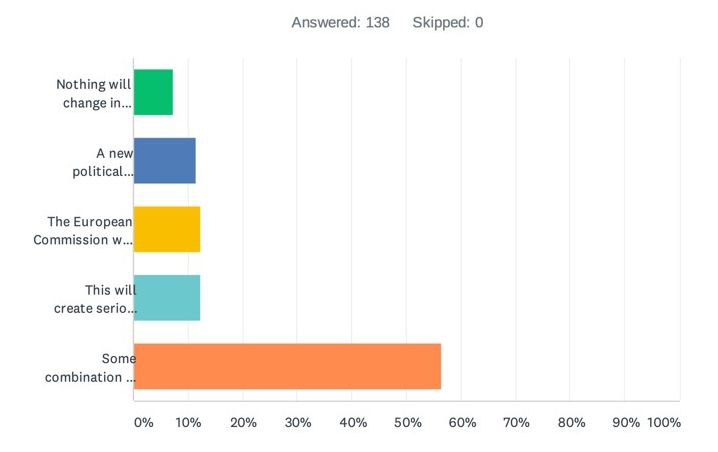

Question 9: What are your views on the mostly likely consequences of the Schrems II ruling?

Again, respondents were provided with a variety of possibilities here: (i) Nothing will change in practice – organisations will transfer data as they always have done, (ii) A new political solution will be reached soon between the EU and US that will solve these issues, (iii) The European Commission will publish new Standard Contractual Clauses soon that will solve these issues, (iv) This will create serious long term challenges for data transfers out of the EEA/UK, or (v) Some combination of all of the above!

There was a clear winner in this case: Some combination of all of the above, with just under 57% of the responses. What you can read into this is that there is no “magic bullet” that is likely to solve this issue, but that the solution is instead likely to rely on a combination of political negotiations between the EU and US and revised data export solutions from the EU Commission.

Whether those solutions will emerge in the short-to-mid term is something that only time will reveal.

What conclusions can we draw?

The above survey results demonstrate, in stark terms, the significance of the Schrems II ruling: the great majority of respondents are reliant upon US-based (or non-EEA/non-UK based) processors and very few have the intention of reducing or ceasing that reliance, whatever the law may say. There is a clear will on the part of respondents to try to comply with the Schrems II ruling, but the completion of transfer impact assessments in all cases looks unrealistic, and uncertainty persists as to what "supplementary measures" are expected by regulatory authorities.

At the end of the Schrems II ruling, the CJEU denies that its decision is "liable to create … a legal vacuum" (para 202), yet the analysis above would seem to indicate otherwise. Notable data transfer gaps are already well-known to exist, for example, for processor-to-subprocessor data transfers, and direct data collection of EEA/UK data by B2C organisations established in the US – gaps that reliance on Article 49 data export derogations, as the EDPB has made clear, cannot solve in all cases. Added to that, the SCCs – which, as Schrems II affirms, do remain valid – are somewhat outdated, in the sense that they reflect Directive 95/46 standards, and not current GDPR standards.

The positive news is that politicians and regulators seem to have heeded this message: dialogue is reportedly ongoing between the US and EU to address the consequences of Schrems II, the Commission is working on updated SCCs, and the EDPB plans further guidance in the coming months. In the meantime, the results would indicate that non-EEA/non-UK data transfers will continue, albeit with more commercial friction, pending effective and realistic regulatory clarity – clarity that, more than ever, is sorely needed.