Locations

In the recent case of Fromageries Bel SA v J Sainsbury Plc [2019] EWHC 3454 (Ch), the High Court has ruled that the well-known Babybel 3D trade mark is invalid for failing to specify the hue of the colour red.

Read the full ruling here.

Background and Legal Basis

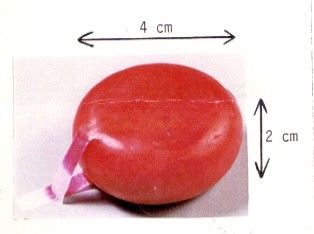

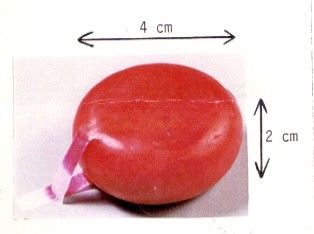

In 1997, Fromageries Bel SA (FBSA) registered a three-dimensional shape mark in the UK under class 29 in relation to cheese.

The image above was accompanied by the description 'The mark is limited to the colour red. The mark consists of a three-dimensional shape and is limited to the dimensions shown above.'

In October 2017, J Sainsbury PLC applied to invalidate the Babybel mark on the grounds that it did not satisfy either section 3(1) and section 3(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994. The Hearing Officer at the UKIPO's Trade Mark Registry found that the mark was invalidly registered and the registration was cancelled (see Decision O/086/19). FBSA therefore appealed to the High Court.

Legal Recap: Trade Marks Act 1994

1. Under section 3(1)(a) a sign should not be registered as a trade mark if it does not satisfy the requirements of section 1(1).

Under section 1(1) a trade mark is a sign which is capable:

(a) of being represented in the register in a manner which enables the registrar and other competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to the proprietor; and

(b) of distinguishing goods or services from one undertaking from those of other undertakings.

2. Under section 3(2) a sign should not be registered as a trade mark if it consists exclusively of the same (or another characteristic) which results from the nature of the goods themselves; is necessary to obtain a technical result or which gives substantial value to the goods.

UKIPO Decision

As a preliminary step, before considering the various grounds of invalidity put forward by J Sainsbury, the Hearing Officer assessed which were the essential characteristics of the Babybel mark. He decided they were its shape, dimensions and its red colour. Given that the colour was an essential characteristic of the mark, an application to invalidate the mark under section 3(2) failed.

The Hearing Officer went on to address section 3(1)(a) and considered that under s3(1)(a) the colour red should have been defined with more clarity. The Hearing Officer cited the Sieckmann judgment that trade marks should be graphically represented in a 'clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective' manner.

He also cited the Libertel judgment which held that 'descriptions of colours could not be sufficiently clear and precise to satisfy the requirement for graphical representation of colour marks and that internationally recognised colour identification codes should be used'.

The mark was therefore declared invalid on the basis that the picture and accompanying description were not a precise representation of the colour red and that there should have been a specific colour hue.

Basis of the Appeal

FBSA appealed the UKIPO decision in the High Court based on three grounds:

1. The Hearing Officer had erred in applying the Sieckmann criteria to a mark that is not a colour mark per se. The Hearing Officer had erred in failing to interpret the registration as being limited to the red colour shown in the picture in the registration.

2. If the Sieckmann criteria did apply to a mark that is not a colour mark per se and if registration was not already limited by the graphical representation, FBSA should be permitted to limit the registration to the specific shade of red Pantone No. 193C under section 13(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994.

Appeal decision

Application of the Sieckmann criteria to colour per se marks

The court held that the UKIPO's preliminary evaluation of the mark's essential characteristics in order to dismiss invalidity under section 3(2) was neither 'necessary or helpful' given that in this case, invalidity could only be assessed under section 3(1).

The court held that a hue of colour is not always required when a mark is not a colour per se mark, even when the colour is an essential characteristic of the mark. The judgment compared marks such as Coca Cola's use of red, white and silver and Tesco's use of blue and red. In relation to these marks, although the colour is an essential characteristic of the mark 'the precise hue is unlikely to play a significant role in making the mark capable of distinguishing.'

The proper way to determine the need for precision of colour is 'the extent to which the colour of the mark contributes to making the mark capable of distinguishing and whether it is likely that only a particular hue will confer on the mark that capacity to distinguish'. Subsequently, the need for precision of colour in marks, which are not colour per se marks, should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

The court evaluated the evidence and concluded that the Babybel mark could only be distinguishing if a particular hue of red was used on the main product. Therefore, the court came to the same conclusion as the UKIPO, that the representation of the colour red was not precise enough, but for different reasons. The first ground of appeal was dismissed

Was the colour specified by the pictorial representation of the mark?

The court agreed with the UKIPO's finding that the description of the mark and the pictorial representation of the mark were not sufficiently clear and precise. It was felt that if the mark was intended to be limited to the hue of red in the picture, that the description accompanying the picture would have referenced the picture, as the description did so with the shape. Instead, the description merely limits the mark to 'the colour red' and does not specify a hue.

The court noted that if there had been no description at all, it may have been reasonable for an onlooker to assume that the mark was limited to the hue of red in the picture. However, given the contrasting nature of the description and the pictorial representation, the second ground of appeal was dismissed.

Could FBSA apply to limit the mark?

The third ground of appeal was considered by the court to be an application to limit the colour red to Pantone 193C. The court dismissed this application on the basis that it would 'go further and introduce an additional feature into the content of the Trade Mark in order to make it distinctive'. Overall, rather than limiting the description, the alteration would make material changes.

Comment

This decision is a warning to trade mark owners or anyone applying to register a mark, for which colour is a distinguishing element, that colour descriptions should be clear and precise and should specify the particular colour hue for which protection is sought. Trade mark owners should be aware that a pictorial representation of a mark will not necessarily satisfy the Sieckmann criteria in relation to colour elements of a mark, particularly if the accompanying description does not make clear reference to the particular colour hue in the pictorial representation.

The case highlights that trade mark owners must be alert to the stricter registration requirements following a string of recent case law (see our blogs – Red Bull's colour mark still lacks wings and Colour trade marks continue to be chopped down) which confirmed that the Sieckmann criteria are still very much applicable in determining the validity of a trade mark, and this seems to be the case, even when the mark is not a colour mark per se. Trade mark owners would be wise to review their trade mark portfolios to assess whether their current trade marks might be vulnerable to invalidity challenges.

With special thanks to trainee, Emma Varty, for her contribution to this blog.

Background and Legal Basis

In 1997, Fromageries Bel SA (FBSA) registered a three-dimensional shape mark in the UK under class 29 in relation to cheese.

The image above was accompanied by the description 'The mark is limited to the colour red. The mark consists of a three-dimensional shape and is limited to the dimensions shown above.'

In October 2017, J Sainsbury PLC applied to invalidate the Babybel mark on the grounds that it did not satisfy either section 3(1) and section 3(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994. The Hearing Officer at the UKIPO's Trade Mark Registry found that the mark was invalidly registered and the registration was cancelled (see Decision O/086/19). FBSA therefore appealed to the High Court.

Legal Recap: Trade Marks Act 1994

1. Under section 3(1)(a) a sign should not be registered as a trade mark if it does not satisfy the requirements of section 1(1).

Under section 1(1) a trade mark is a sign which is capable:

(a) of being represented in the register in a manner which enables the registrar and other competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to the proprietor; and

(b) of distinguishing goods or services from one undertaking from those of other undertakings.

2. Under section 3(2) a sign should not be registered as a trade mark if it consists exclusively of the same (or another characteristic) which results from the nature of the goods themselves; is necessary to obtain a technical result or which gives substantial value to the goods.

UKIPO Decision

As a preliminary step, before considering the various grounds of invalidity put forward by J Sainsbury, the Hearing Officer assessed which were the essential characteristics of the Babybel mark. He decided they were its shape, dimensions and its red colour. Given that the colour was an essential characteristic of the mark, an application to invalidate the mark under section 3(2) failed.

The Hearing Officer went on to address section 3(1)(a) and considered that under s3(1)(a) the colour red should have been defined with more clarity. The Hearing Officer cited the Sieckmann judgment that trade marks should be graphically represented in a 'clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective' manner.

He also cited the Libertel judgment which held that 'descriptions of colours could not be sufficiently clear and precise to satisfy the requirement for graphical representation of colour marks and that internationally recognised colour identification codes should be used'.

The mark was therefore declared invalid on the basis that the picture and accompanying description were not a precise representation of the colour red and that there should have been a specific colour hue.

Basis of the Appeal

FBSA appealed the UKIPO decision in the High Court based on three grounds:

1. The Hearing Officer had erred in applying the Sieckmann criteria to a mark that is not a colour mark per se. The Hearing Officer had erred in failing to interpret the registration as being limited to the red colour shown in the picture in the registration.

2. If the Sieckmann criteria did apply to a mark that is not a colour mark per se and if registration was not already limited by the graphical representation, FBSA should be permitted to limit the registration to the specific shade of red Pantone No. 193C under section 13(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994.

Appeal decision

Application of the Sieckmann criteria to colour per se marks

The court held that the UKIPO's preliminary evaluation of the mark's essential characteristics in order to dismiss invalidity under section 3(2) was neither 'necessary or helpful' given that in this case, invalidity could only be assessed under section 3(1).

The court held that a hue of colour is not always required when a mark is not a colour per se mark, even when the colour is an essential characteristic of the mark. The judgment compared marks such as Coca Cola's use of red, white and silver and Tesco's use of blue and red. In relation to these marks, although the colour is an essential characteristic of the mark 'the precise hue is unlikely to play a significant role in making the mark capable of distinguishing.'

The proper way to determine the need for precision of colour is 'the extent to which the colour of the mark contributes to making the mark capable of distinguishing and whether it is likely that only a particular hue will confer on the mark that capacity to distinguish'. Subsequently, the need for precision of colour in marks, which are not colour per se marks, should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

The court evaluated the evidence and concluded that the Babybel mark could only be distinguishing if a particular hue of red was used on the main product. Therefore, the court came to the same conclusion as the UKIPO, that the representation of the colour red was not precise enough, but for different reasons. The first ground of appeal was dismissed

Was the colour specified by the pictorial representation of the mark?

The court agreed with the UKIPO's finding that the description of the mark and the pictorial representation of the mark were not sufficiently clear and precise. It was felt that if the mark was intended to be limited to the hue of red in the picture, that the description accompanying the picture would have referenced the picture, as the description did so with the shape. Instead, the description merely limits the mark to 'the colour red' and does not specify a hue.

The court noted that if there had been no description at all, it may have been reasonable for an onlooker to assume that the mark was limited to the hue of red in the picture. However, given the contrasting nature of the description and the pictorial representation, the second ground of appeal was dismissed.

Could FBSA apply to limit the mark?

The third ground of appeal was considered by the court to be an application to limit the colour red to Pantone 193C. The court dismissed this application on the basis that it would 'go further and introduce an additional feature into the content of the Trade Mark in order to make it distinctive'. Overall, rather than limiting the description, the alteration would make material changes.

Comment

This decision is a warning to trade mark owners or anyone applying to register a mark, for which colour is a distinguishing element, that colour descriptions should be clear and precise and should specify the particular colour hue for which protection is sought. Trade mark owners should be aware that a pictorial representation of a mark will not necessarily satisfy the Sieckmann criteria in relation to colour elements of a mark, particularly if the accompanying description does not make clear reference to the particular colour hue in the pictorial representation.

The case highlights that trade mark owners must be alert to the stricter registration requirements following a string of recent case law (see our blogs – Red Bull's colour mark still lacks wings and Colour trade marks continue to be chopped down) which confirmed that the Sieckmann criteria are still very much applicable in determining the validity of a trade mark, and this seems to be the case, even when the mark is not a colour mark per se. Trade mark owners would be wise to review their trade mark portfolios to assess whether their current trade marks might be vulnerable to invalidity challenges.

With special thanks to trainee, Emma Varty, for her contribution to this blog.