Locations

Historically, finance houses have based their lending decisions on financial performance, asset class and relationship, with investors looking primarily on their returns as the measure of success.

But as pressure continues to mount on governments and businesses to compel social and environmental change in light of damning reports on the impact of climate change amidst challenging global economic circumstances, ‘socially responsible investments’ are becoming de rigeur.

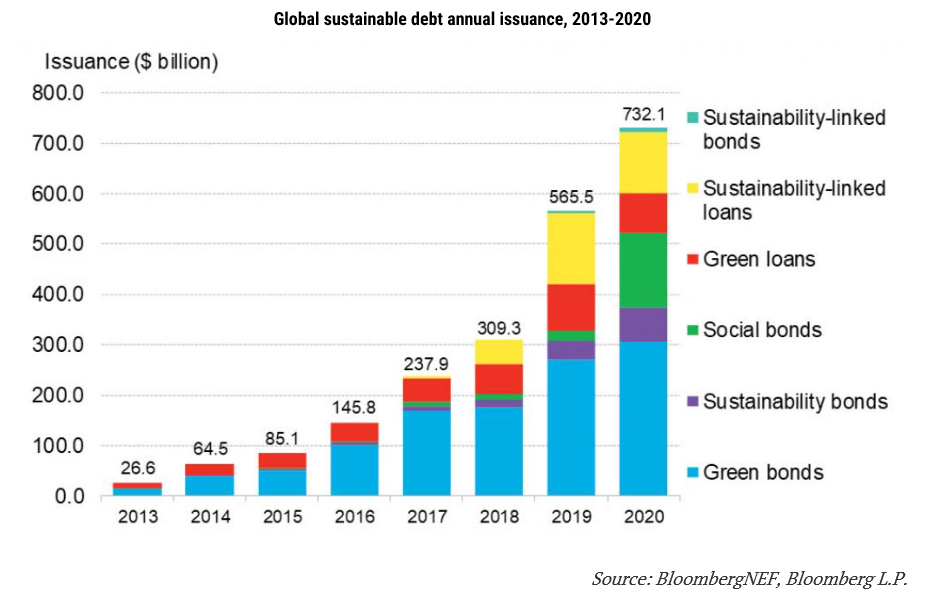

Whilst undeniably ‘in fashion’, a passing trend this is not. According to Bloomberg, over $700 billion of sustainable and green debt instruments were issued in 2020, notwithstanding the dampening effect of COVID-19 on the debt markets generally – that's up from $250 million in 2018.

Climate change may still be a matter of debate for some, but its elevation into mainstream public consciousness is undeniable. The COVID-19 pandemic and its related issues, along with other fast paced social change, show us that a fundamental shift in attitudes is afoot. The rise of sustainable finance is perhaps therefore unsurprising – but what is it and is it here to stay?

What is sustainable finance?

Sustainable finance refers to any form of financial service which integrates ESG criteria – environmental, social and governance – into business or investment decisions. In the world of sustainable finance, there is a wide range of terminology in use without any uniform definition. It is therefore perhaps useful to refer to the European Commission's description of ESG in its 2018 "Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth"

| Environmental | Refers to climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the environment more broadly and its related risks (for example, natural disasters) |

| Social | Refers to inequality, inclusiveness, labour relations and investment in human capital and communities |

| Governance | Relates to the governance of public and private institutions, including management structures, employee relations and executive remuneration, and plays a "fundamental role in in ensuring the inclusion of social and environmental considerations in the decision-making process". |

Since 2015, there has been a steady stream of new law and regulation in this area, attempting to embed ESG in the financial markets. This article is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the regulatory position, but you can find a summary of the regulatory aspects as at the end of 2020 here. For members, the Loan Market Association also regularly updates its Sustainable Lending microsite for those keen to better understand the regulatory position.

Broadly, sustainable debt instruments fall into the following categories:

- Green bonds (used for climate and environmental projects).

- Sustainability bonds (used to finance or refinance ‘green’ or ‘social’ projects).

- Social bonds (used for projects with positive social outcomes).

- Sustainability-linked loans (the cost of the loan is linked to predetermined sustainability objectives).

- Green loans (also used for ‘green’ purposes).

Green bonds, the oldest of the sustainable debt instruments, make up the lion’s share of the market to date, with issuances rising 13% in 2020. Only last month, Atrium European Real Estate raised four times its €300 million target for its inaugural green bond.

The new kids on the block - green and sustainability linked loans – are also on the rise, albeit issuance reduced slightly in 2020, thought to be due to COVID-19 related disruption.

Commentators credit the rise in popularity of these products, not only to changing global circumstances and pressures, but to the implementation of new law, industry engagement and the publication of applicable industry guidelines, which have helped to shape the parameters of sustainable finance and mitigate the risks of 'green washing', which we discuss below. However, whilst regulatory considerations are 'nudging' the ESG agenda, financial institutions are committing pots of capital on a voluntary basis for ESG purposes, due largely to investor expectations amidst strong evidence of the link between sustainability and value.

The Loan Market's response to Sustainable Finance

The Loan Market Association ("LMA") is the trade body for the EMEA syndicated loan market. It has fully engaged with the ESG agenda, offered support in correspondence with regulators (for example in its letter to the European Banking Authority in January 2021) and, as mentioned above, has its own dedicated Sustainable Lending microsite. The LMA, the Loan Syndications and Trading Association (LSTA) and the Asia Pacific Loan Market Association (APLMA) also published the "Green Loan Principles" and the "Sustainability Linked Loan Principles", aiming to promote the development and integrity of these loan products to facilitate and support environmentally sustainable economic activity and to provide a high level framework of market guidelines. In its March 2021 monthly update, the LMA also described the work it is undertaking on new "Social Loan Principles" (SLP) in response to rapid growth in this space arising as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. An update on the SLP is here.

To date, the loans market has (as stated above) adopted two main products: green loans and sustainability linked loans.

What is the difference between a ‘green loan’ and a ‘sustainability-linked loan’ (‘SLL’)?

There are fundamental differences between green loans and SLLs.The proceeds of a green loan must be applied for ‘green’ purposes. The LMA has published guidance by way of a non-exhaustive list of green projects for which a green loan can be used.

By contrast, an SLL can be used for any purpose – but the pricing on the loan is linked to predetermined sustainability objectives that incentivise the borrowing company to improve its performance against ESG criteria, i.e. the cost of the loan is directly linked to the sustainability performance of the borrower.

The key characteristics of each are set out in the table below and the principles examined in more detail in the next section.

| Green loan | SLL | |

| Purpose | To promote environmentally sustainable growth and reduce the impact of new lending activities on the environment | To promote environmentally and socially sustainable growth and incentivise businesses to commit to sustainability |

| Use of proceeds | Proceeds must be used for green projects only | Unlimited |

| Pricing | Pricing not linked to any particular objectives | Pricing linked directly to sustainability objectives |

| Principles | The LMA sets out four key principles which underpin the loan characteristics:

|

The LMA sets out four key principles which underpin the loan characteristics:

|

What are the principles and why are they important?

As the popularity of green and sustainable investments has risen, one of the criticisms levelled at the market is that, in the absence of recognised market standards, certain products may be labelled as ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ when in reality they are little different than an ordinary debt instrument. This is called ‘green washing’ – a form of marketing that portrays an organisation as producing positive environmental and social outcomes when this is simply not the case.

As mentioned above, in an attempt to tackle these issues, the LMA developed the Green Loan Principles and the Sustainability Linked Loan Principles. These are designed to promote the development and integrity of the market and give confidence to investors. Whilst the principles are voluntary, the idea is that they will be widely adopted which will engender investor confidence in green and sustainable products.

Green Loan Principles

- Use of Proceeds: the loan must be utilised for green projects which provide clear environmental benefits.

- Process for Project Evaluation and Selection: the borrower should make it clear to the lenders the process by which it determines how its projects fit within the acceptable categories of green project, and the eligibility criteria which is applied.

- Management of Proceeds: the proceeds of a loan should be credited to a dedicated account (or equivalent process) to maintain transparency as to how they are applied.

- Reporting: borrowers should maintain up to date records on the use of proceeds and where possible, to report on achieved impacts.

Sustainability Linked Loan Principles

- Relationship to Borrower’s Overall CSR Strategy: the borrower should clearly communicate to the lenders its sustainability objectives as set out in its CSR strategy and how these align with the sustainability performance targets (‘SPT’) (to which the loan is linked).

- Target Setting – Measuring the Sustainability of the Borrower: the SPT should be ambitious and meaningful to the borrower’s business. Third party opinions may be sought as to the appropriateness of the SPTs as a condition precedent to completion.

- Reporting: borrowers should maintain up to date records on their SPTs and provide these to the lenders at least once every year. Public reporting is encouraged to facilitate transparency.

- Review: For publicly traded companies, lenders may be comfortable relying on the borrower’s public disclosures to verify its performance. Otherwise, borrowers may be required to seek external review of its performance.

How does a company measure its ESG successes?

In addition to the problems presented by the absence of recognised standards in sustainable finance, one of the key issues facing companies keen to participate in sustainable debt products is how to measure sustainability within their business. As demand for higher transparency on ESG issues across sectors and jurisdictions has risen, a number of different frameworks and standards which seek to set out how sustainability can be measured have emerged.

However, the plethora of different tools available makes it difficult to identify a commonly accepted standard and any comparison or benchmarking almost impossible. It is therefore likely that we will see more development and standardisation in this area, in a bid to improve measurability and transparency.

In the world of real estate, performance measurement has improved significantly in just a few short years, with the Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark (GRESB) improving the value of sustainable investment tangibly. The GRESB offers, "high quality ESG data and powerful analytical tools to benchmark ESG performance, identify areas for improvement and engage with investors".

It is also possible to obtain a rating or score from a third party agency, in much the same way as Moody's or S&P might rate a company or institution from a credit perspective. The GRESB, for example, offers assessment and rating services for both fund managers and underlying assets. Bloomberg also provides a sustainability ratings service. The methodology, scope and coverage of such assessments across different agencies vary greatly, however, which has led to criticism of the credibility of such ratings. It is likely that, as recognised sustainability standards emerge, and ESG disclosure improves, such ratings will become a more valuable way of assessing sustainability performance.

What does sustainability look like for different asset classes?

Given the long life-cycle of most real estate assets, what we build today will have long-term implications for both mankind and the planet. Thankfully, there are many different ways in which sustainability can be incorporated into both the development and management of real estate assets. In the development of new assets, maximising building efficiency, flexibility and resilience can look relatively straightforward, and we already have recognised standards for buildings efficiency such as BREEAM and energy performance certificates. Changing practices or structures in existing buildings can be more difficult and expensive, but may ultimately be necessary over the long-term to ensure the longevity and continuing relevance of those buildings.Both green loans and SLLs are relevant to new or existing buildings - even if a business or asset has no track record of ESG, sustainable finance can be used to develop that asset or business into one with ESG at its core. The market shifts we have seen in the past year due to the pandemic give rise to new opportunities in both new and existing buildings. The rapid decline of retail, for example, presents investors with a unique chance to repurpose existing retail space with sustainability in mind – for commentary on the repurposing of assets, please refer to our article 'Repurposing Retail'.

The following table sets out just a few examples of how sustainability might feature in a sustainable debt product for a particular asset.

| Asset class | Green loan | SLL |

| Commercial office space | Proceeds of loan to be used for:

|

Cost of loan linked to:

|

| Logistics | Proceeds of loan to be used for:

|

Cost of loan linked to:

|

| Retail | Proceeds of loan to be used for:

|

Cost of loan linked to:

|

| Residential/ student accommodation | Proceeds of loan to be used for:

|

Cost of loan linked to:

|

| Hospitality | Proceeds of loan to be used for:

|

Cost of loan linked to:

|

How is sustainable debt documented?

As yet, there is little by way of standardisation in terms of the ESG-specific clauses you might expect to see when agreeing to a green or sustainable loan. However, standardisation is one of the current LMA initiatives in this area, and so we expect that some form of precedent documentation will take shape during 2021.There are other ongoing initiatives which aim to move the market towards standardisation from an ESG perspective – The Chancery Lane Project, for example, has published a 'playbook' which has a number of very helpful 'LMA style' clauses which may be adapted to reflect the agreed terms of a green loan or SLL. The playbook covers a wide variety of commercial contracts, not just those relating to debt finance.

For the moment, at least, parties to credit agreements are agreeing such provisions on a bespoke basis and in accordance with the unique goals they have set to improve their own ESG performance.

Notwithstanding the lack of standardisation however, ESG specific contractual provisions in credit agreements are likely to cover the following key elements:

- for green loans, amendments to the 'purpose' clause to identify the green projects to which the loans are to be applied;

- for SLLs, details of the agreed sustainability KPIs which the borrower must meet for any margin (or other cost) adjustments;

- ongoing undertakings on the borrower to provide ESG related information and reporting;

- ESG reporting to be in the form of a stand-alone agreed compliance certificate scheduled to the credit agreement;

- references and representations to a borrower's internal policies and procedures, which will look similar to a bribery or sanctions covenant;

- conditions precedent which cover ESG requirements, for example, building and design certifications;

- if required by a lender, third party verification or ratings confirmations (for example, by a third party ratings agency)

Is sustainable finance 'the future'?

As already mentioned in this article, the uptake in sustainable finance is likely to continue on its current trajectory. Regulatory and public pressure will be a key driver in further growth, and businesses which do not have sustainability at their core will ultimately become obsolete unless they adapt – making adoption mandatory, rather than optional.A number of long-term commitments from lenders to providing sustainable finance will serve to solidify that growth. For example, HSBC have committed to deploying between $750m-$1trn of sustainable finance in the next 10 years. In 2019, Goldman Sachs pledged $750 billion over the next decade for large opportunities in sustainable finance.

It is becoming widely accepted that such pledges are not being made just from an ideological standpoint, but because they make sense from a business perspective. Public calls to action, governmental initiatives and investor appetite dictate that companies will need to start demonstrating that they are ‘doing their part’ in the sustainable revolution – or risk falling out of favour with customers and investors alike.