Locations

AGA's trade marks, but not its copyright, were held to be infringed in an instructive judgment for those involved with upcycling and refurbishment activities, handed down by the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) on 8 July 2024 (Aga Rangemaster v UK Innovations & McGinley).

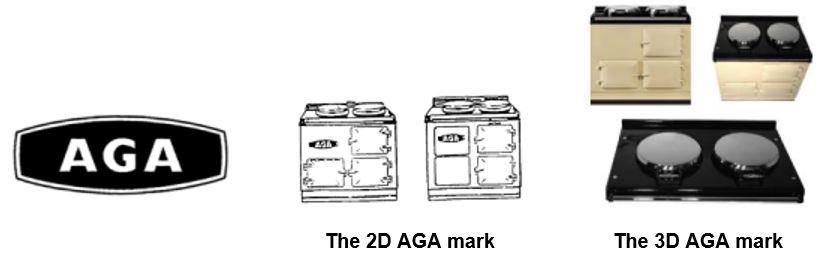

AGA Rangemaster Group (AGA) owns numerous trade marks in respect of its range cookers, including AGA word marks and the following:

Mr McGinley, the second defendant, developed an electronic control system for range cookers (the eControl system), to convert them from fossil fuels to electricity. He was a director of UK Innovations, the first defendant, which refurbished and sold AGA range cookers to which it had retrofitted the eControl system. The cookers retained their AGA badges as well as their original look, save for the replacement of the original temperature gauge with an 'eControl system' badge.

AGA sued for trade mark and copyright infringement, claiming against UK Innovations as primary infringer and Mr McGinley as accessorily liable.

1. Trade mark infringement: did the defendants have a defence?

AGA sued for trade mark infringement on all three grounds of s10 Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA), that is:

- Identical marks/identical goods and services (s10(1) TMA);

- Identical/similar marks, identical/similar goods and services plus likelihood of confusion (s10(2)TMA); and

- Identical/similar marks, any goods and services, where mark has a reputation and use without due cause is detrimental to or takes unfair advantage of the distinctive character or repute of the mark.

The defendants did not deny that their activities fell within s10 TMA except in respect of the 2D AGA mark, but argued they did not infringe because:

- s12 TMA gave them a defence; AGA's rights in the trade marks were exhausted in the cookers which AGA had previously placed or authorised to be placed on the market;

- ss11(2)(b) & (c) TMA gave them defences as they had used the AGA marks descriptively and/or to indicate that the eControl system was used to convert genuine AGA cookers;

- their actions were not such as to infringe the 2D AGA mark in any event; and

- the 2D and 3D AGA marks were invalid.

The s12 TMA defence: were AGA's rights exhausted?

At the time of the infringing acts, the exhaustion defence set out in s12 TMA provided, essentially, that where goods had been put on the market with AGA's consent, it could only object to the use of its trade marks in relation to those goods where it had "legitimate reasons" for doing so, which included where the condition of the goods had been changed or impaired1.

This decision makes clear that the bar for what level of change or impairment is required to amount to a legitimate reason to object is set quite high. It is not enough that customers may believe that there is a connection between the parties – if it were, that would mean that the exhaustion defence could never apply to infringement cases under s10(2), which requires a likelihood of confusion, or s 10(1) where the defendant's acts affect the origin function of the trade mark.

Neither is it enough on its own that there has been a change in condition of the goods or damage to the reputation of mark.

The judge (Nicholas Caddick KC, sitting as a Deputy High Court judge) considered in depth the extent of the works which had taken place to the AGA cookers, categorising them into "refurbishment works" (to restore the cooker to original-level condition) and "conversion works" (to convert the cooker from gas/oil to electricity). He noted that the cookers were very long lasting and expensive products, comprising many working parts.

On the refurbishment works, he concluded that "customers would understand that, if they buy [an AGA] second hand, it is likely to contain replacement parts and I do not think that those customers would assume that such original parts must necessarily be of the same quality as the original parts". On the conversion works, he noted that AGA did not object to the defendants supplying eControl systems to be fitted to AGA cookers, and so it was hard to see how it could object to a cooker to which the system had been fitted coming onto the market for sale, and equally hard to see how it could object to the defendants fitting those systems to cookers and then re-selling them. There was little risk of any of the refitted cookers reflecting poorly on AGA, as customers who knew they were buying a second hand, refurbished cooker would not necessarily associate quality issues with AGA itself.

Neither the refurbishment works nor the conversion works in themselves gave AGA legitimate reasons to object to further dealings in the trade marked goods.

The judge then went on to consider "the way in which the Defendants marketed and sold the eControl cookers", and this is what gave the claimant legitimate reasons to object to the defendant's activities. On their website and invoices, the defendants had made multiple references to "eControl AGA", "Controllable Aga Cookers", "Aga colours" and so on, alongside (on the website) pictures and line drawings of AGA cookers. There was nothing which made it clear to a reasonably attentive customer that the defendants were not connected to the claimant, and "these statements taken as a whole were likely to give customers the impression that what they were being offered was an AGA product (an eControl AGA, one of a range of AGA products)". This was something which AGA could legitimately object to, and for this reason, the s12 defence was not available to the defendants.

Post sale confusion – not a legitimate reason to object

Many recent cases consider post sale confusion (see for example our recent blog here: A game of two halves: Umbro prevails in diamond mark infringement appeal | Fieldfisher), which can lead to a finding of infringement based on how the mark is perceived by others, not necessarily the customer, after sale. Here, any post sale confusion did not give rise to a legitimate reason to object to further dealings in the trade marked goods. People seeing the AGA and eControl system marks together after sale, and who had not therefore seen the use of the AGA marks on the website and invoices, would not necessarily assume a connection between the two. It is not unreasonable for someone who has carried out refurbishment works to put their label onto the product to indicate their work and indeed it is probably preferable for that to be done where the condition of the goods has been changed, as here. This therefore did not provide a legitimate reason for AGA to object to further dealings of the cookers.

The s11 TMA defence: were the defendants using the marks to refer to the purpose of the products?

Section 11 TMA2 provides that a trade mark is not infringed by so-called 'referential use'. This includes use of the trade mark to refer to the goods as being those of the trade mark proprietor where it is necessary to indicate, for example, the purpose of the goods, so long as it is used in accordance with honest practices. This was the subject of a reference to the CJEU recently, and although post-Brexit the ruling does not form part of English law, our law in this area has not diverged from EU law and therefore the ruling is influential (see our blog on this ruling here: Running rings around referential use of trade marks: the CJEU's decision in Audi v GQ | Fieldfisher).

The judge gave short shrift to the defendants' arguments that s11 gave them a defence. Their use of the AGA marks was not descriptive but was distinctive use as part of a badge of origin. The use suggested an association with AGA, as set out above, and given the alteration of the goods had nothing to do with AGA, the use of the marks to identify the goods as being those of AGA was not in accordance with honest practices.

Infringement of the 2D & 3D AGA marks

The defendants claimed, irrespective of any defences they may have had, that they did not infringe the 2D AGA mark as 1) they had not used those signs in relation to goods, 2) their signs were not similar to that mark, and 3) a disclaimer to that mark, "Registration of this mark shall give no right to the exclusive use of the device of a cooker", had the effect of negating the mark's protective effect. These arguments were roundly rejected and the defendants' activities fell squarely within ss10(1) and 10(2) TMA (as to s10(3), see below).

The same arguments were raised regarding the 3D AGA mark, but they had not been pleaded properly and were rejected in any event.

s10(3) TMA infringement

As the defendants had put AGA to proof on its claimed reputation, the judge looked at whether AGA had made out reputation, and decided it had clearly shown "a very considerable reputation" in its marks. While the defendants' activities were not detrimental to the repute of those marks, they were detrimental to and took unfair advantage of the distinctive character of those marks, without due cause.

The defendants had infringed AGA's marks under each of ss10(1), 10(2) and 10(3) TMA, and they had no defence under either s11 or s12 TMA.

2. Invalidity

The defendants' claims that the 2D and 3D AGA marks were invalid failed. They had argued that both marks failed the test in s1(1) TMA as they were not signs capable of being trade marks, and that the 3D AGA mark failed s3(2) TMA, as it consisted exclusively of shapes resulting from the nature of the goods, or which are necessary to obtain a technical result, or which give substantial value to the goods.

The marks were however held to be sufficiently clear and precise to fall within s1(1) TMA. The 2D AGA mark would be understood by the relevant public as a two dimensional representation of a three dimensional object, so there was no lack of certainty as to what the mark consisted of. The visual and verbal representations of the 3D AGA mark, contrary to the defendants' arguments, were not inconsistent with each other and that mark was also sufficiently clear and precise.

The judge disagreed that the shape of any of the essential characteristics of the 3D AGA mark was exclusively due to the nature of the goods themselves, or was necessary to obtain a technical result, or gave substantial value to the goods, and therefore that mark did not fall foul of s3(2) TMA.

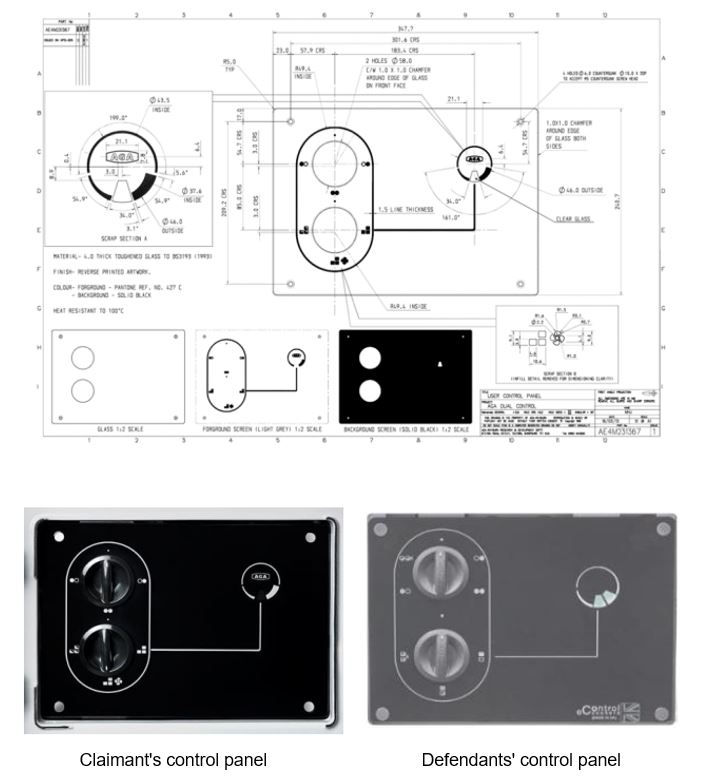

3. Copyright infringement

AGA claimed copyright infringement relating to a computer assisted design drawing showing the design of the control panel for its electric AGA cookers; see below, along with photographs of AGA's and the defendants' control panels:

The drawing attracted copyright, being an artistic work which was its author's own intellectual creation and was therefore original. Although functional considerations had been taken into account in creating the drawing, they did not dictate the drawing; several other designs could have performed the function, and there was still room for creative freedom.

Furthermore, the defendants had copied a substantial part of the drawing, even if indirectly by copying the control panel itself.

However, there was no infringement of copyright due to the operation of s51 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA). That section states:

"It is not an infringement of any copyright in a design document … for anything other than an artistic work … to make an article to the design or to copy an article made to the design".

The parties had not addressed this provision in any depth and so the judge worked his way through an analysis of the pertinent issues himself. His conclusion was that s51 CDPA did operate and so the copyright in the drawing had not been infringed. The drawing was an artistic work, but was a design document for something other than an artistic work, so it was not an infringement for the defendants to copy either the drawing or the cooker (the article made to the design) by making their control panels to the design.

The judge then went on to consider the purpose of s51 CDPA and whether the CJEU's judgment in Cofemel impacted the provision, concluding that it was not possible "to reach any final conclusion as to the impact of Cofemel on s51. Instead, … I will deal with the s51 issue simply on the basis of its own wording". His previous conclusion that s51 operated to exclude infringement here stood.

4. Joint tortfeasance

We are increasingly seeing directors being joined to infringement proceedings as joint tortfeasors alongside their companies, and after the Supreme Court's judgment on this topic in Lifestyle Equities v Ahmed (see our recent article here: A sigh of relief for company directors as the Supreme Court rules that accessory liability requires knowledge | Fieldfisher), this trend is likely to continue.

A point of difference between this case and the Ahmed case is that for copyright infringement, unlike for trade mark infringement, there is no requirement for the infringing acts to be done in the course of trade. The judge speculated that Mr McGinley could have been liable as a primary infringer and not just as an accessory, as he had actually copied the design, and under s16(2) CDPA, one can be liable as a primary infringer either for doing the act or for authorising it, without the need to show that the act was done in the course of one's own trade. This was of course irrelevant here as there was no copyright infringement.

Ahmed is clear that for someone to be liable for a tort as an accessory, they must know the essential facts which make the tort wrongful; they must know that 1) the acts will be done and 2) they are an infringement. This case had been heard before the Ahmed Supreme Court judgment had been handed down, and therefore the pleadings and evidence did not directly address the issue of Mr McGinley's knowledge regarding the acts which infringed AGA's trade marks. The judge navigated this as best he could and found that although Mr McGinley had some of the requisite knowledge, there were "numerous vital facts which have not been shown to have been known to Mr McGinley", and on that basis he was not a joint tortfeasor in the trade mark infringement.

Comments

Much has been written recently about whether intellectual property rights could inhibit upcycling or refurbishment of goods, and therefore whether they may be environmentally detrimental. This case however makes it very clear that such activities are not in themselves problematic. What was unacceptable here was the perceived connection between the parties, which makes one wonder whether the use of a clear disclaimer that there was no commercial connection to AGA may have got the defendants off the hook.

Also of note is that the evidence showed that only 26 of the eControl System cookers had been sold. One wonders therefore whether AGA may have been more motivated by the principle of the action rather than its financial impact on AGA's bottom line.

Footnotes

1 s12 TMA:

(1) A registered trade mark is not infringed by the use of the trade mark in relation to goods which have been put on the market in the United Kingdom or the European Economic Area under that trade mark by the proprietor or with his consent.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply where there exist legitimate reasons for the proprietor to oppose further dealings in the goods for the purpose of protecting the proprietor's property (in particular, where the condition of the goods has been changed or impaired after they have been put on the market).

2 s11 TMA:

[…]

(2) A registered trade mark is not infringed by—

(a) …

(b) the use of signs or indications which are not distinctive or which concern the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, the time of production of goods or of rendering of services, or other characteristics of goods or services, or

(c) the use of the trade mark for the purpose of identifying or referring to goods or services as those of the proprietor of that trade mark, in particular where that use is necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a product or service (in particular, as accessories or spare parts),

provided the use is in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters.