Locations

The court also permitted Lidl to rely on survey evidence at trial to prove distinctiveness of its marks (Lidl Great Britain Limited v Tesco Stores Limited [2022] EWHC 1434 (Ch)). The substantive claims for trade mark infringement, copyright infringement and passing off will be heard at the main trial at a later date.

Background

Lidl is a budget supermarket, known for its discount prices and cheaper 'knock-off' brands. It is the sixth largest supermarket in the UK, whilst Tesco sits at the top as the largest supermarket in the country.

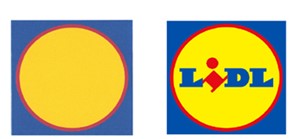

Lidl owns various registered trade mark rights for two versions of their logo: a graphical device consisting of a blue square background bearing a yellow disk, bordered in a thin red line ("the Wordless Mark") and the graphical device with the word "Lidl" within the yellow disk ("the Mark with Text") as shown below:

'The Wordless Mark' 'The Mark with Text'

Tesco's loyalty 'Clubcard' allows holders to shop at often massively discounted prices. To promote these discounted prices, Tesco uses a blue square background containing a yellow disk, with the words "Clubcard Prices" within the disk ("the Sign") as shown below:

The 'Sign' The Sign as used with text

The claims

Lidl claimed that Tesco's use of the Sign infringed their registered trade marks. Lidl accepted that the Wordless Mark had not been used on its own in the UK, but because it had been used in conjunction with the Mark with Text, it was recognised in the UK as being distinctive of Lidl's business. Consequently, the Wordless Mark had a reputation in the UK and Tesco was taking unfair advantage and was 'seeking deliberately to ride on the coattails of Lidl’s reputation as a "discounter"'. Alternatively, the use of the Sign was detrimental to the distinctive character of the Wordless Mark, contrary to section 10(3) of the TMA 1994. Lidl did not plead confusion under section 10(2) TMA 1994.

Lidl also claimed passing off because Tesco had misrepresented that its products shared the qualities of Lidl's products including that they were the same or equivalent prices or had been price-matched with Lidl's products. Lidl also claimed copyright infringement in the artwork of both the Wordless Mark and the Mark with Text.

The counterclaim

Tesco counterclaimed to revoke or declare invalid Lidl's Wordless Mark, claiming that the Wordless Mark was a 'figment of Lidl's legal imagination and a product of its filing strategy', which 'did not exist in the real world'. Tesco argued it had been registered in bad faith and/or lacked distinctiveness. Tesco argued that Lidl had applied for the Wordless Mark with no intention to use it, but instead to hold it as a 'legal weapon' over others. Tesco also accused Lidl of 'evergreening' as demonstrated by duplicative protection applied for in 2005 and even in 2021, after legal proceedings had commenced.

In terms of lack of distinctiveness, Tesco claimed that the Wordless Mark was never distinctive in the first place and because it had never actually been used by Lidl to confer any distinctiveness through use, consumers would not rely on that mark alone to indicate the origin of Lidl's goods and services, as required by law.

The strike out and survey evidence applications

Lidl applied to the High Court to strike out the defendants' counterclaim on bad faith, or alternatively, for summary judgment.

In order to strike out the counterclaim, the court must find that there are no reasonable grounds for bringing the claim, and the claim was certainly bound to fail. (CPR 3.4(2)(a) along with CPR 3.4(1)).

Lidl also requested permission to rely on survey evidence to argue the marks' distinctiveness.

Decision

Bad faith

The judge set out various principles established in case law on bad faith, including:

- Lack of intention to use a trade mark may, in some circumstances, be relevant to, and evidence of bad faith (Sky plc v Skykick UK Ltd (Case C-371/18)). However, according to Sky Limited v Skykick UK Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 1121 ('Skykick'), 'lack of intention to use, on its own, does not amount to bad faith'.

- Skykick established that bad faith as a ground for invalidity requires use of the trade mark registration system 'which would be regarded in commerce ("in the course of trade") as not in accordance with honest practices or acceptable commercial behaviour'. That would be the case where the trade mark right was sought for reasons other than those falling within the functions of a trade mark.

- It was established in Walton International Ltd v Verweij Fashion BV [2018] EWHC 1608 (Ch) that there is a presumption of good faith unless the contrary is proved. An allegation of bad faith is a serious allegation, which must be distinctly proved; the standard of proof is the balance of probabilities but cogent evidence is required due to the seriousness of the allegation.

- Walton International also stated that consideration must be given to the trade mark applicant's intention.

Though Tesco argued that Lidl had never used and never intended to use the Wordless Mark given they were relying on the Mark with Text to show use of the Wordless Mark, the judge referred to Specsavers International Healthcare Ltd v Asda Stores Ltd (C-252/12) [2013] ETMR 46 (which had explored the use of a trade mark in a form differing in elements which did not alter the distinctive character), which stated that there was nothing wrong with owning overlapping trade mark registrations, or protecting a background of a logo that they considered to be distinctive. There was nothing wrong with the wider monopoly created in doing that.

Tesco's allegations of bad faith based on "evergreening" by Lidl were also found to be insufficient. Despite Lidl applying to re-register the Wordless Mark, it was evident that they did this upon their own "commercial rationale": the colours were updates, they covered a wider specification of goods, and they covered wider territories. There was no evidence to suggest bad faith and the allegation that the Wordless Mark was merely a 'legal weapon' was no more than an assertion.

Overall, Tesco was unable to establish reasonable grounds for making the bad faith allegation. Tesco's pleading was not sufficient to shift the evidential burden to Lidl to provide a plausible explanation of its objectives and commercial strategy in relation to the applications for the Wordless Marks. Further, there was no proof that Lidl's 'sole objective' when applying to register the Wordless Mark was for purposes outside the essential functions of a trade mark. Lidl's application to strike out Tesco's counterclaim of bad faith was therefore ultimately approved by the High Court.

Survey evidence

Lidl had applied to the High Court for permission to rely on survey evidence at trial in respect of its own activities, reputation and marks. Tesco objected to the admissibility of the survey questioning its value, its reliability and also the fact that it had carried out the survey without obtaining permission from the court in advance.

In support of Tesco's claim that Lidl's survey had no value, they argued that it had used the 'wrong stimulus' and been 'conducted under artificial circumstances' because Lidl had shown the 'Wordless Mark' to participants which had never been used in the real world. Lidl's view was that this was not a flaw, but rather an important feature to test the distinctiveness of the logo. The fact that participants associated the mark with Lidl in absence of text proved that consumers understood the background element of the logo to be connected with the goods and services of Lidl.

In terms of unreliability, Tesco criticised the survey for not having complied with a number of the "Whitford Guidelines".

These guidelines, (as set out by Whitford J in Imperial Group plc v Philip Morris Ltd [1984] and subsequently endorsed by the Court of Appeal in Interflora v Marks & Spencer [2012] EWCA Civ 1501), established the rules for the conduct of a survey which would be capable of assisting the court at trial, such as that: (i) in order for the survey to be valid, it was necessary to interview a relevant cross-section of the public; (ii) any survey had to be of a size that was sufficient to produce a relevant result viewed on a statistical basis; (iii) the party relying on the survey had to give the fullest possible disclosure of the number of surveys and people involved; (iv) no leading questions; (v) exact answers must be recorded with no abbreviations; (vi) the totality of all answers should be dislclosed; and (vii) the instructions given to interviewers must be disclosed. Judges must also find that the costs of admitting the survey to courts are justified and proportionate to the case itself, and that the survey has real value as evidence (Zee Entertainment v Zeebox Ltd [2014] EWCA Civ 82).

Having analysed the relevant case law, the judge's view was that the survey evidence was likely be of real value to the court in assessing both recognition and whether there was an understanding on the part of the participants of the nature of the image that they were being shown, i.e. that it was an identifier of origin.

They highlighted the 'intrinsic value' of the evidence and permitted Lidl to rely on it in trial. The judge also felt that in this particular case, the issue of distinctiveness was not one which the judge at trial would necessarily feel able to determine on their own using their own knowledge and experience. Further, despite Lidl not seeking permission of the court prior to carrying out the survey, it was not reason enough to exclude the evidence in court.

Tesco estimated their costs to be around £136,000 if the survey evidence was found admissible. The judge found this 'wholly unrealistic' and considered Lidl's estimation of around £64,000 to be more favourable. The judge reiterated that there was no apparent reason why Lidl would not be allowed to rely upon the survey in court and the value of the survey justified the cost.

Comment

There have been several supermarket spats in recent years – think back to the battle of the caterpillar cakes between M&S and Aldi as one example. However, these disputes are usually initiated by the bigger supermarkets against the smaller discount supermarkets allegedly ripping off their products. This case is the other way round with Lidl taking on the leading supermarket in the UK. This tactical move highlights the importance of the case to Lidl in a challenging marketplace in which Lidl believes Tesco is trying to associate itself with Lidl's discounted products.

The review and analysis of both the law on bad faith and survey evidence will be helpful for practitioners.

The case is a useful reminder that an allegation of bad faith is a serious one and amounts to allegations of commercial dishonesty, so it is very important that the allegations are, as stated by the judge, 'distinctly pleaded and distinctly proved'. If not, any bad faith allegations may be at risk of being struck out at an early stage. The law on bad faith has continued to evolve over the past few years and shows no signs of abating with Sky v Skykick now heading to the Supreme Court.

The case provides a useful reminder of the relevant case law on survey evidence and how to assess whether such evidence is of real value and can assist the court at trial. The case also highlights the unpredictability of courts' decisions on the admissibility of evidence at trial. The judge in this case made it clear that every case must be decided on its own facts and the fact that in this instance she allowed the survey evidence, despite Lidl not having requested permission from the court in advance, is not blanket approval for not seeking permission. It really depends on the circumstances.

It will be interesting to see whether the survey evidence does offer real value in the substantive proceedings and how much weight it is given by the judge when assessing distinctiveness of Lidl's marks.

We will report back so watch this space!

With special thanks to vacation student, Salma Eleyan, for her contribution to this article.