Fantastic trade marks and where to find them

This month the CJEU hiked into the little-travelled hinterland of contemporary IP law on the trail of a particularly quirky and rarely-glimpsed creature – the position trade mark.

Background

Disputes relating to non-traditional trade marks have been the staple form of popular entertainment for IP lawyers over the last five years as a number of iconic shape marks and colour marks withered under scrutiny of the higher courts. We saw the 3D trade mark for the iconic London taxi written off and left abandoned on the hard shoulder. We saw Kit Kat's famous fingers crumble in their awkwardly opaque packaging. We saw Cadbury grudgingly surrender its registration for the colour purple after a protracted battle.

However, position trade marks are the Iberian lynx of the IP forest, so rare as to be virtually unknown beyond their own unique niche. The EUIPO recently received its two millionth EU trade mark application. However, according to the EUIPO database there are only 115 applications classified as "position marks", since that categorization was introduced on the EUIPO database in 2017. Over the same period, there were 833 new applications for 3D trade marks and over 125,000 for word marks. 86 of the applications for position marks remain live and 38 of those, around 44% of the total, are in class 25 and cover apparel products.

What is a position trade mark?

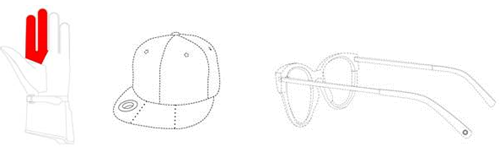

So what is a position trade mark and why do apparel businesses find them valuable? A registered position trade mark protects a feature as applied to a given product in a specific and distinctive position. Here are some examples filed during the last year, all of which remain under examination.

Why are position marks useful?

Why is the concept of a position mark particularly useful to apparel businesses? It is now several decades since apparel businesses realised that, by wearing their products, customers can become – in effect – walking billboards for the brand. The first iteration of this approach was the development of externally visible apparel branding: names and logos on the front of clothing. Ralph Lauren's visibly branded polo shirts in the early 1970s are an example and the trend became widespread through the 1980s, particularly as sportswear began to merge with fashion. It became normal to wear a brand name across your chest.

However, names and logos only take you so far. Most IP lawyers would not wear a Nike branded t-shirt to a client meeting, however much they like the brand. Position trade marks allow businesses to protect other features that, while less complex than logos or names, can still be recognised and understood by consumers if used consistently and in a specific way.

Munich SL's mark

The position trade mark that came before the CJEU this month is particularly venerable. It is owned by Munich SL, a footwear business founded in Barcelona in the 1930s, and protects a black cross as applied to the side of a shoe, which Munich has been using since the mid-1960s. The EUTM representation is shown below.

The application was filed 17 years ago in 2002 and was registered in 2004. Munich had sought to enforce the EUTM registration against Deichmann, a well-established footwear retailer based in Essen and trading throughout Europe. Deichmann retaliated by seeking to revoke Munich's EUTM on the grounds of non-use in proceedings before the EUIPO. Inevitably, the matter ended up before the CJEU.

Deichmann's argument

Deichmann's argument is a subtle one. The application had been filed as a "figurative" trade mark. The application form had four options: "marca denominativa", "marca figurativa", "tridimensional" and "otro" (word mark, figurative mark, 3D mark and 'other'). Munich's representative had ticked the second box. On this basis, Deichmann argued, the mark should be construed as a figurative mark and used in that way. Since Munich had used the black cross on shoes but had not used an image of the whole stylised shoe, dotted lines and all, it had not used the mark "as registered" and could not defeat the revocation action.

It is noted that at the time of filing, prior to the 2017 reforms, 'position trade mark' was not explicitly listed as an option, although the application could have been classified under 'other'.

General Court's decision

The General Court did not accept Deichmann's argument. The court found that the technical classification of a given application should not override the characteristics of the mark as represented. It also found that there is a degree of overlap between figurative marks and position marks, and that it was clear from the representation that the dotted lines should be understood as enabling the position of the cross to be specified, as is common in trade mark representations. On this basis, it construed the registration as protecting a position mark and found that Munich's use of the black cross on the side of various shoes over the years constituted genuine use of the mark as registered.

CJEU ruling

Deichmann's sole ground of appeal before the CJEU was that the General Court had erred in law by failing to give proper weight to the administrative classification of the application as a figurative mark rather than a position mark. The CJEU did not accept Deichmann's arguments. It pointed out that position marks had not been officially defined at the time of filing and there was no explicit classification for those marks. Furthermore, the court agreed with the General Court that the starting point for assessing a trade mark was the representation of that mark. If the representation satisfied the Sieckmann criteria in being clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective, and was also readily understood as a position mark, then it was appropriate to apply the case-law relating to position marks when assessing it.

The CJEU also rejected Deichmann's argument that unless the dotted lines in the representation had been explicitly disclaimed, then they should be considered a part of the mark as filed. The court pointed out that there is no obligation under EUTM law to add written descriptions or disclaimers. The court did, however, acknowledge that more recent EUIPO guidance suggests that position marks should be explicitly specified, although it pointed out that such guidance is not itself legally binding. In any event, Deichmann's appeal failed and Munich's EUTM remains registered. (See the CJEU judgment in this case C‑223/18 P.)

Comment

Overall, the CJEU's judgment is a reminder that what matters first and foremost in matters of EU trade mark law is the representation of the mark. The administrative classification of mark type, as with the Nice classification of goods and services, is just that – an administrative aid rather than an artificial constraint on the fundamental nature of the right identified. When assessing a position mark, like any other trade mark, the key questions are whether the representation clearly specifies an identifiable brand identifier, whether that brand identifier can be distinctive of commercial origin and whether its use is consistent with that purpose.

Potential applicants for position trade marks do still need to proceed with some caution. Since 2017, the EUIPO has had an explicit classification for position trade marks and the official guidance does ask that applicants make use of this classification to explicitly identify position trade marks at the time of filing. We would certainly recommend that applicants follow this advice and avoid the ambiguities with which Deichmann tried to bring down Munich's registration. However, the fact that position marks, and a range of other rare beasts such as motion marks, pattern marks and hologram marks, are now explicitly dealt with in the EUIPO's procedures since 2017 may also make it more attractive for businesses to explore those less trodden paths. And for the applicant who is determined to break a completely new trail in search of mythical IP beasts, the EUIPO still has that magical, unexplored category "Other".