Locations

Background

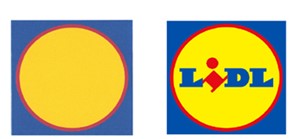

In a reversal of the usual roles, supermarket giant Tesco has been accused of trade mark infringement of the following marks by its smaller discount competitor Lidl:

'The Wordless Mark' 'The Mark with Text'

The case is based on Tesco's use of the sign below for promoting discounts through its loyalty "Clubcard":

The 'Sign' The Sign as used with text

Tesco has retaliated with counterclaims against the Wordless Mark for invalidity based on Lidl's bad faith, or for revocation based on non-use. In the first round of this dispute, (which we reported here: Lidl victory against Tesco in relation to bad faith counterclaim and survey evidence), the High Court found that Tesco was unable to establish reasonable grounds for making the bad faith allegation against Lidl.

The decision on appeal

On appeal, Lord Justice Arnold examined the points at issue in detail.

Mark applied for solely for deployment as a legal weapon

Arnold LJ disagreed with the High Court's finding that it was "no more than an assertion" that the Wordless Mark was applied for by Lidl solely for deployment as a legal weapon, pointing out that all allegations in statements of case are assertions by the parties as to the facts. He went on to say that Lidl could have adduced evidence to show that this factual assertion was manifestly unsustainable, but it had not done so. Therefore, Lidl had failed to justify the allegation being struck out and it must be assumed to be true until argued at trial.

Arnold LJ further stated that, absent an admission, the subjective intention of a party is usually a matter of inference from the objective facts, and bad faith was no different in that respect. He found that Tesco's allegation that the mark was applied for solely for deployment as a legal weapon was a permissible inference from the pleaded facts, which stated that:

1. the Wordless mark had never been used;

2. there was no intention to use this mark; and

3. use of the Mark with Text did not amount to use of the Wordless Mark.

Even if use of the Mark with Text demonstrated use of the Wordless Mark, that would have no bearing on the bad faith nature of the application because, in that case, there would have been no need to apply for the latter separately, unless the purpose of such an application was to give Lidl wider or different protection, something that Lidl itself confirmed.

Contrary to Lidl's submissions, Arnold LJ found that the inference could not be disproved merely by the counter-assertion that Lidl was entitled to obtain a wider scope of protection than conferred by registrations of the Mark with Text. Whether obtaining that wider scope of protection was legitimate required an investigation of the facts.

Lidl's filing strategy – an abuse of the trade mark system?

Arnold LJ confirmed that where an applicant seeks unjustifiably broad trade mark protection, that may amount to an abuse of the trade mark system which constitutes bad faith. Whether it does so may depend on the facts and the applicant's intentions. He reached the conclusion that Tesco had made a sufficiently arguable case, such that the circumstances gave rise to a real prospect of the presumption of good faith being overcome, so as to shift the evidential burden to Lidl to explain its intentions.

He noted that the High Court failed to recognise that Tesco's case was not based on the mere existence of an overlapping mark but that its claims, as noted above, had a real prospect of success.

Arnold LJ found that Tesco had sufficiently pleaded its claim to raise a prima facie case that Lidl had periodically re-filed applications duplicating coverage for the Wordless Marks – so-called evergreening – in order to circumvent the trade mark non-use provisions. Furthermore, Lidl's attempt to rebut this allegation by claiming it was extending the geographical scope of protections by filing EU trade marks did not provide a sufficient answer, due to its repeat re-filings.

Comment

The outcome of this appeal demonstrates that, although the bar may be set high in proving bad faith in trade mark invalidity cases, the bar for admitting such allegations will be set relatively low, necessitating a full examination of the facts at trial.

There have been a number of recent cases concerning issues of bad faith relating to the filing of overly broad specifications, evergreening and the lack of intention to use (for example the Sky v Skykick dispute which is heading to the Supreme Court and the Monopoly cases (see our blogs: The end of trade mark 'monopolies'? Defeat for Hasbro in an important General Court decision on evergreening and Do not pass Go, do not collect £200, do not register trade marks in bad faith)), so it will be interesting to see how the facts of this case play out at trial in light of such decisions.

The case raises a number of points that may give trade mark owners cause to re-evaluate their trade mark protection strategies so they are not left vulnerable to challenge.

The trial is expected to be scheduled early next year so watch this space for further updates.