Locations

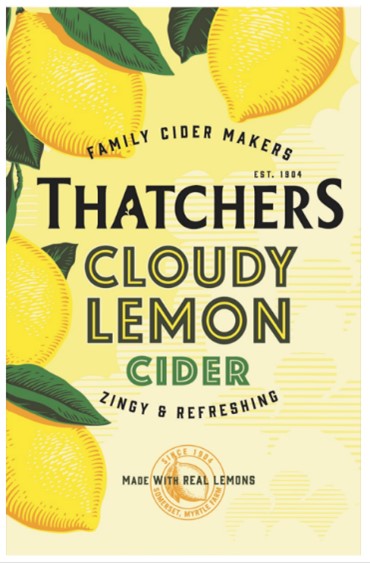

In an about turn from the IPEC decision, which we blogged about here, the Court of Appeal, (Thatchers Cider Co Ltd v Aldi Stores Ltd [2025] EWCA Civ 5), has found in favour of Thatchers, holding that Aldi's lookalike cloudy lemon cider packaging does infringe Thatchers' trade mark for the get-up of its own cloudy lemon cider.

Lord Justice Arnold, with Lord Justice Philips and Lady Justice Falk agreeing, found Aldi had intentionally taken unfair advantage of Thatchers' reputation in its mark by using a sign that reminded consumers of the trade mark to convey the message that its product was "like the Thatchers Product, only cheaper".

Background

Thatchers, the long established cider maker, launched its cloudy lemon cider and registered a UK device trade mark depicting the label in 2020. This product was extensively promoted and sold well. Aldi launched its own cloudy lemon cider product under its Taurus brand in May 2022. In September 2022, Thatchers commenced proceedings in the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court ("IPEC") claiming trade mark infringement pursuant to Section 10(2) (likelihood of confusion) and Section 10(3) (reputational grounds) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 ("TMA") plus passing off.

The Court found that the alleged infringing sign was visually similar to the registered mark to a low degree, and was aurally and conceptually different. Furthermore, the court was not satisfied that Aldi intended to exploit the reputation and goodwill of Thatchers' trade mark. In a novel approach, the judge tasted the competing products and concluded that they were not so significantly different that Aldi's product would cast Thatchers' product in a negative light. Therefore, Thatchers' claims were dismissed.

1. Thatchers' registered trade mark | 2. Thatchers' mark, as used on its packaging

Aldi's cloudy lemon cider packaging

The Appeal

Thatchers did not dispute the judge's findings that there was no evidence of misrepresentation to support the claim for passing off, nor that, in the absence of any real evidence of confusion by consumers, there was no real likelihood of confusion. Instead it focused its appeal against the judge's decision that, notwithstanding its reputation in the mark, Aldi's product did not take unfair advantage of this reputation and nor did it cause detriment (or tarnishment) to that reputation.

Don't miss a thing, subscribe today!

Stay up to date by subscribing to the latest Intellectual Property insights from the experts at Fieldfisher.

Subscribe nowCourt of Appeal Decision

The Sign

The first point for consideration was the judge's identification of the sign to be compared ("Sign"). The Court of Appeal found that the judge had erred in identifying the Sign as Aldi's product, rather than the design printed on the front and rear of each can and on the cardboard packaging of its product.

Leading on from this, the Court of Appeal noted that it is acceptable to make a single assessment of similarity between Sign and Trade Mark under s10(2) TMA (likelihood of confusion) and s10(3) TMA (reputational grounds), as long as the other relevant factors under s10(3) were not conditioned by factors only relevant to s10(2). This was because the purpose of the assessment differs under the respective grounds, with the similarity between the marks being such that it leads of a likelihood of confusion under s10(2), as compared to assessing whether the similarity between the marks leads to a link between them in the minds of consumers and consequent damage to reputation under s10(3). Here the judge had not erred in making such a single assessment on similarity but had erred in finding that a point of difference was that the Sign was three-dimensional and the Trade Mark was two-dimensional. Consequently, she should have assessed the similarity between the marks as being greater, taking into account Thatcher's actual use of the sign on its packaging.

Was there a link?

Turning to whether the average consumer would make a link between the signs at issue and whether this would lead to unfair advantage, Arnold LJ addressed this with reference to Aldi's intention. He found the judge, at first instance, had confused, or at least had failed to distinguish between, an intention to deceive consumers, necessary under s10(2) and an intention to take advantage of the reputation of the trade mark under s10(3). She had also erred in finding that Aldi had not significantly departed from its Taurus house style in the design of the lemon cider packaging (the other flavours had a very different look to the cloudy lemon flavour), and had been wrong to discount the faint horizontal lines present in both the Trade Mark and the Sign, because she felt they would go unnoticed by consumers.

The Court of Appeal found that Aldi's packaging closely resembled that of Thatchers and that this was no coincidence, since other third party products on the market clearly showed it was possible to convey that a beverage was lemon-flavoured without such a close resemblance. The colour change to the Taurus house style, the inclusion of prominent images of lemons and leaves and the reduced prominence of the "swooshes" on the Aldi Product represented a "manifest departure" from Aldi's usual Taurus house style. Although the faint horizontal lines may go unnoticed by consumers (relevant for the s10(2) assessment of similarity), these should not have been discounted when assessing Aldi's intention to take advantage. Arnold LJ agreed with Thatchers that "it is often the reproduction of inessential details which gives away copying". Evidence relating to the design process and Aldi using the Thatchers Product as the sole product for benchmarking purposes also helped with coming to the inescapable conclusion that Aldi intended the Sign to remind consumers of the Trade Mark to convey the message that the Aldi Product was "like the Thatchers Product, only cheaper", thereby intending to take advantage of Thatchers' reputation in its cloudy lemon cider to assist in selling the Aldi Product. That consumers would not be deceived or even confused as to trade origin did not detract from this.

Was there unfair advantage?

Before looking at the issue of whether the advantage taken by Aldi was unfair, the Court of Appeal examined the judge's findings that the sales achieved by Aldi for its cloudy lemon cider product were not disproportionate to those of other ciders in the Taurus range. However, Arnold LJ found that the Aldi Product achieved significant sales in a short period of time without any promotion and Aldi had not put forward any evidence to show it would have made that volume of sales without use of the Sign but rather with a design consistent with the house style of the rest of the Taurus range.

The judge had rejected Thatchers' arguments that this was a classic case of unfair advantage by transfer of image, like that in L'Oréal v Bellure, without giving reason, so the Court of Appeal had to consider this afresh. It found Thatchers was correct that the present case squarely fell within the EU Court of Justice's description in L'Oréal v Bellure of a "transfer of the image of the mark" and "riding on the coat-tails of that mark". As noted, Aldi had intended to take advantage of the Trade Mark to sell its own product. It was clear from social media evidence that at least some consumers had received the message that the Aldi Product was "like the Thatchers Product, only cheaper", and there was no reason to think they were atypical.

Furthermore, Aldi had been able to achieve substantial sales of the Aldi Product in a short period "without spending a penny on promoting it". In the absence of evidence that it would have made like sales without use of the Sign, and hence without consumers linking the Sign with the Trade Mark, it was legitimate to infer that Aldi thereby obtained the advantage from the use of the Sign that it intended to obtain. That was an unfair advantage because Aldi was able to profit from Thatchers' investment in developing and promoting the Thatchers Product, rather than competing purely on quality and/or price and on its own promotional efforts.

The Court of Appeal rejected Aldi's position that any advantage was not unfair and that Thatchers' claim under s10(3) involved overreach because the only distinctive element of the Trade Mark was the word THATCHERS. It came to this conclusion because the Trade Mark had achieved registration, and reputation had been found in it, which was not solely linked to the word THATCHERS and was in fact distinct from any reputation in THATCHERS alone. The judge at first instance had found a link between the Sign and the Trade Mark, even if this did not lead to consumer confusion. The findings as a whole put this case in line with the L'Oréal v Bellure case, with Aldi's conduct amounting to exactly the kind the law is designed to protect trade mark owners from. Thus the appeal was allowed against the judge's conclusion that Aldi's use of the Sign did not take unfair advantage of the reputation of the Trade Mark.

Was there detriment to repute?

Arnold LJ noted that the Aldi Product was not the same quality as the Thatchers Product, but there was no evidence consumers had been misled so as to regard the Thatchers Product less favourably. Consumers would likely see this as one explanation for the Aldi Product being cheaper. Consequently, The Court of Appeal agreed with the earlier decision that there was no detriment (or tarnishment) to the reputation in the Thatchers Trade Mark.

Did Aldi have a defence?

Since Aldi was successful at first instance, the judge had felt there had been no need to examine its defence under s11(2) TMA that all of the similar aspects of the Sign and the Trade Mark were descriptive or otherwise non-distinctive. The Court of Appeal thought it worth considering in case its findings were wrong. It found it was wrong to dissect the Sign into its constituent elements and argue that because some of those elements were descriptive, the Sign as a whole fell within s11(2). In reviewing all the relevant circumstances, the Court found that Aldi's use was not in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters because it was unfair competition.

As a last resort, Aldi had argued that the Court should depart from the L'Oréal v Bellure case (being EU-derived law), but Arnold LJ felt this would not be appropriate. There had been no repeal or amendment of s10(3) so the law continues to be harmonised with the EU, unless divergence is appropriate because the Court of Justice's interpretation is erroneous, but that was not so. Decisions must be on a principled basis and the Court of Justice's ruling in L'Oréal v Bellure provided such principled basis. It was not an isolated decision and had been built on and developed by a number of the Court's decisions of persuasive authority. Departure would cause considerable legal uncertainty and the decision in that case neither restricted proper development of the law nor turned it in the wrong direction. Furthermore, the Court pointed to other international treaties aimed at harmonising trade marks, and declined to depart from EU law.

Comment

Trade mark owners may feel that the Court of Appeal's decision here has shifted the balance back in their favour. But do marks have stronger or broader protection in light of this decision? The appeal concerned a mark with reputation but presumably, where lookalike products are concerned, retailers will only be interested in sailing close to brands with sufficient reputation. Here Thatchers had a trade mark registration for a whole label and reputation in this was recognised, so it perhaps has broader protection than many word or logo only marks or where reputation has not been established.

Arguably cases such as this are fact specific to some extent so would not necessarily have blanket applicability. However, where a trade mark owner has a reputation in a brand, this case reinforces the point that the lookalike need not be confusingly similar to infringe, and the case may give brand owners renewed confidence to bring actions.

Trade mark owners should consider whether the registration of get-up trade marks, and the promotion needed to earn a reputation, are warranted. Supermarkets and other retailers should consider what they need to do to ensure they stay the right side of the lookalike line, such as taking care with benchmarking and exercising caution in departing from house styles without clear justification. There has been no legislation on this specific area, nor does any look imminent, and the Court of Appeal itself would not be drawn on the policy considerations between protecting brand owners from lookalike packaging and arguments that such practices support better competition and lower prices for consumers. Therefore, although this case looks to be a win for brand owners, supermarkets, and particularly the discount retailers, are unlikely to stop pushing the boundaries with lookalike brands. We doubt this will be the last case of this type.